A (not so) brief foreword: this essay was originally commissioned by an independent publisher looking to release an anthology on gender. In 2017 they asked if I’d be interested in writing an essay on womanhood. I was a little surprised, the publisher being explicitly queer and me being a radical feminist, but ultimately pleased: their goal was to publish a collection with plural perspectives on gender, and I believe wholeheartedly that having the space for plural perspectives on any issue is essential for healthy, open public discourse. I knew that my lesbian feminist essay would probably be in a minority standpoint, and felt comfortable with it being published alongside contradictory perspectives. Given the extreme polarity of gender discourse, which results in a painful stalemate between queer activists and radical feminists, it was encouraging to think we had reached a point where multiple views could be held and explored together.

So I wrote the essay, made the requested edits, and produced a final draft with which the publisher and I were both delighted. Their words: “We’re really happy with the edits you’ve done and the areas you’ve developed on upon our request. You did a splendid job refining the essay.” However, certain people objected to the inclusion of my essay before having read it. Some early readers gave the feedback that they were unhappy to find a perspective that they were not expecting, and alarmed that I had connected my personal experience of gender as a woman to the wider sociopolitical context we inhabit. Backlash escalated to the point that the publishing house faced the risk of having their business undermined and their debut collection jeopardised.

They gave me the option of writing another essay for the gender anthology, or having this essay published in a future collection. I declined both choices, as neither felt right – fortunately, there are more projects on my horizon. That being said I have great sympathy for the publisher’s position, and find it regrettable that their bold and brilliant venture should be compromised by the very people it was designed to support. Furthermore, I wish the publisher every success with this project, and all future endeavours. As for the essay, controversial even before being read, I have instead decided to publish it here as the seventh part of the series on sex, gender, and sexuality. It is, in my opinion, a good essay and deserves to see the light of day.

If you enjoy or learn from this essay, and can afford to do so, please consider donating to cover the lost commission of this work. [UPDATE: the publisher has offered partial payment depending on the success of their crowdfunding campaign. Thank you to everyone who has supported me. It means a great deal.]

Where there is a woman there is magic. If there is a moon falling from her mouth, she is a woman who knows her magic, who can share or not share her powers. – Ntozake Shange

I absolutely love women. I love women in a way that leaves me breathless, in a way that catches just behind my ribs and gently tugs at my heartstrings until they unravel. I love women with a depth and fervour that is fundamentally lesbian. And in loving women I find extraordinary reserves of strength, the will to keep on challenging white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks, 1984), the motivation to chip away at every hierarchy and oppression that acts as a pillar upholding the ills of society. A love of women is central to my feminism, for bonds between women – links of solidarity and sisterhood in particular – have a revolutionary power unequal to any force on this earth.

According to Adrienne Rich, “the connections between and among women are the most feared, the most problematic, and the most potentially transforming force on the planet.” The connections shared by women, and all that flows across connections between women, open the possibility for radical social change – which is why lesbian existence and feminist politics are complimentary forces in a woman’s life.

Loving women as I do, I have spent a great deal of time musing upon what it is to be a woman, from where the appeal of women springs. As many young lesbians do, I speculate about the nature of the draw which compels us to watch all sorts of random crap on television simply because the middle-aged actress we fancy has a small role in the production. Having grown up in this world as a girl and subsequently learned how to negotiate this world as a woman, I have also reflected upon the social and political significance of the category – the weight which is undeniable. The question of what it means to be a woman has been central to feminist discourse for hundreds of years: establishing what womanhood is, pinpointing the means and motive behind woman’s oppression under patriarchy, and working out how to end that oppression are central feminist concerns.

At present the feminist movement is split in two over how to conceptualise woman and woman’s oppression. The tensions between queer ideology and sexual politics have proven every bit as divisive as the sex wars of the 1980s. The source of the split lies within gender – specifically, whether gender ought to be conceptualised as a hierarchy or as an identity within feminist analysis. Feminists have historically identified gender as the means of women’s oppression: patriarchy is reliant on gender to establish and maintain a hierarchy that enables men to dominate women. But by the turn of the century queer theorists such as Judith Butler and Jack Halberstam began to suggest that gender may be subverted and experimented with until the very fabric of society is no longer recognisable.

Owing to the mainstreaming of queer ideology, we have entered an unprecedented era governed by the logic of postmodernism – a time in which the relationship between the physical body and material reality is untethered by the politics of identity. As such, those engaging with the progressive politics – be they liberal or radical – begin asking ourselves anew: what does it mean to be a woman?

Woman as a Sex Class

A key element of feminist analysis is the recognition of woman as a sex class. By this I do not mean that all women’s experiences meet the same universal standards, or that all women are positioned similarly within the world’s power structures: factors such as race, disability, social class, and sexuality all shape where a woman is situated in relation to power. Rather, this perspective offers an acknowledgement of the role in which patriarchy plays in determining the power dynamic between women and men. Women’s struggle against patriarchy is collective, and emancipation from systemic oppression cannot be found through individualising a structural issue. Women of all colours and creeds, women of all classes and castes, are actively subjugated from birth – a political analysis which fails to incorporate this reality cannot truly be thought of as feminist. Women’s oppression is a direct result of having been born female-bodied into a patriarchal society. Considering woman as a sex class is, therefore, fundamental to meaningful feminist critique of patriarchy.

This mode of analysis – radically feminist analysis – can grate when misapplied by white women who seek to deny any difference between women’s lives. But when carried out correctly, with rigour and consideration, it has the potential to change the world.

My own womanhood is hardly conventional, Black and lesbian as it is. I do not meet white Eurocentric standards of female beauty or womanhood and no longer aspire towards those standards, which are rooted in racism and misogyny. Owing to skin pigmentation and hair texture, my Blackness is impossible to conceal – even if it were possible, having begun to unpick the misogynoir I have internalised from an early age, I would not choose to hide it in order to assimilate. To be visibly Other is to live with an increased vulnerability, to be perpetually open to manifestations of structural oppression. For a time I despised both my Blackness and my womanhood as a result of the painful alienation misogynoir brought into my life. I have since learned to place the blame firmly where it belongs, with the source of these cruelties: white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy. Since embracing radical politics I have learned to love both Blackness and womanhood, to love myself as a Black woman, in a way that was never possible during my pursuit of conventional beauty standards.

My lesbian presentation (Tongson, 2005) is a further rejection of those beauty standards. I style my hair in a fashion that is distinctly lesbian and have maintained a crisp undercut since coming out. At various points certain members of my family have attempted to enforce compulsory heterosexuality by shaming any outward presentation of a lesbian aesthetic, endeavouring to guide me back into the feminine role. I am told that returning to conventionally feminine presentation would render me “softer”, “more approachable”, and closer to the ideal of beauty. And while I could choose to pass for heterosexual, allowing an assumption that I am available and receptive to men to cushion me from a degree of marginalisation, I do not. I have no desire to appear soft or approachable, least of all to men – the oppressor class. Alice Walker proclaimed that “resistance is the secret of joy”, and she was quite right: there is a feeling of pure elation that flows from resisting the trap and trappings of heteropatriarchy.

Like every single woman living in a patriarchal society, I experience systematic oppression as a consequence of being female. Women – all women – are bound by the rigidity of the gender role ascribed to us on the basis of our biological sex. We are socialised from birth to be soft, compliant, nurturing so that we are primed to adopt the caring role required for upholding the domestic sphere owned by a man, be he husband or father. As Mary Wollstonecraft notably lamented, women are actively discouraged from pursuing our full potential as self-actualised human beings. Instead, women are subjected to a deliberate social (and often economic) pressure designed to create in us an ornamental source of sexual, reproductive, and domestic labour for men.

From Sojourner Truth to Simone de Beauvoir, there is a long and proud tradition of feminists critiquing the role of femininity. During her time as an abolitionist orator, Truth deconstructed womanhood to great effect, asking “ain’t I a woman?” Arguing against the hierarchies of race and gender that determined how the category of woman was understood in North American society during the heights of the transatlantic slave trade, Truth offered her own story as testimony to the falsehood of femininity. Truth used her own strength and endurance as empirical evidence, asserting that womanhood was in no way dependent on or related to the characteristics which construct femininity. Her opposition to gender essentialism and white supremacy continues to influence feminists’ perspectives on womanhood to this very day.

Feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir further critiqued femininity, connecting the socialisation of gender to the oppression of women by men. She theorised that man was the normative standard of humanity and woman understood purely in relation to him:

Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.

That woman is relegated to the Other, lacking in positive definition, mandates a life that is male-centric. If woman exists as the negative image of man, she is forever bound to him. Self-definition has long been recognised as a necessary tool for the liberation of an oppressed group, and if women remain dependent on men for definition then the root cause of our oppression can never be fully tackled. Adrienne Rich once claimed that “until we know the assumptions in which we are drenched, we cannot know ourselves” – as is often the case, her words contain more than a little truth.

Gender is normalised through essentialism, positioned as a natural and inevitable part of life. From the get-out-of-accountability-free card that is ‘boys will be boys’ to the constant refrain of “she was asking for it” when men act upon the cultural conditioning that assures them they are entitled to women’s bodies, the hierarchy of gender maintains the gross power imbalance at the root of sexual politics. Here is how I understand the connection between biological sex and gender roles:

Gender is a socially constructed trap designed to oppress women as a sex class for the benefit of men as a sex class. And the significance of biological sex cannot be disregarded, in spite of recent efforts to reframe gender as an identity rather than a hierarchy. Sexual and reproductive exploitation of the female body are the material basis of women’s oppression – our biology is used as a means of domination by our oppressors, men.

We teach boys to dominate others and disavow their emotions. We teach girls to nurture others at the expense of their own. And I think this world would be a better place if we encouraged more empathy in boys and more daring in girls. If gender were abolished, if we raised boys and girls in the same way, patriarchy would crumble. Like a great many feminists before her, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie advocates the elimination of gender:

The problem with gender is that it prescribes how we should be rather than recognising how we are. Imagine how much happier we would be, how much freer to be our true individual selves, if we didn’t have the weight of gender expectations… Boys and girls are undeniably different biologically, but socialisation exaggerates the differences, and then starts a self-fulfilling process. – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, We Should All be Feminists

It is impossible to consider the position of women in society, the reality that we are second-class citizens by design of patriarchy, without acknowledging the extent of the harm done by gender. Womanhood is caught up in the constraints of the feminine gender role, prevented from escaping male dominion. In the abolition of gender lies a radical alternative. In the abolition of gender lies women’s liberation.

Therefore, recent reframing of gender as an innately held identity has proven problematic in ongoing feminist struggle. Gender identity politics rely on essentialism that feminists have fought for hundreds of years, an essentialism that argues women are naturally suited to the means of our oppression. If gender is inherent – a natural phenomenon after all – then the oppression of women under patriarchy is legitimised.

Womanhood

During the second wave of feminism, it was argued that woman simply meant a biologically female adult human. Feminists (Millett, 1969; French, 1986; Dworkin, 1987) made the case that womanhood could and should exist purely as a biological category, unfettered by the feminine gender role – a vision of women’s liberation. This perspective is directly contradicted by a queer understanding of gender, which primarily focuses on gender as self-expression:

The effect of gender is produced through the stylization of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self. This formulation moves the conception of gender off the ground of a substantial model of identity to one that requires a conception of gender as a constituted social temporality. – Judith Butler, Gender Trouble

A queer notion of gender presents it as a matter of performativity, arguing that dominant power structures may be subverted through transgressing the barriers of masculine and feminine gender roles. Identification with the characteristics associated with a gender role is taken as belonging to the category. Those who identify with the gender role ascribed to their sex class are described as cisgender. Those who do not identify with the gender role ascribed to their sex class are described as transgender. From a queer standpoint, sex is not a fixed category but rather an unstable one. Queer politics are formed gender as a mode of personal identification. Radical feminist analysis, in which gender is understood as a hierarchy, is dismissed as old-fashioned.

If one cannot say with absolutely clarity what is woman and what is man, the oppressed and oppressor classes are rendered unspeakable. Subsequently the hierarchy of gender is made invisible and feminist analysis of patriarchy grows impossible. Without words used as markers to convey specific meaning, women are deprived of the vocabulary required to name and oppose our oppression. Postmodernism and political analysis of power structures make uneasy bedfellows.

Here is where the controversy lies, where gender discourse grows explosive beyond the point of reconciliation between queer and radical feminism. If gender is a matter of personal identification, it is a purely individual matter and, therefore, depoliticised. The power differential between oppressed and oppressor is negated by a failure to consider man and woman as two distinct sex classes. Gender ceases to be visible as a means of oppression, further obscured as the categories of man and woman are considered immaterial. If sex classes are unspeakable, so too are the sexual politics of patriarchy.

If womanhood can be reduced to the performance of the feminine gender role and a personal identification with that gender role, there is little scope for distinguishing between the oppressor and oppressed. Womanhood ceases to be indicated by the presence of primary and secondary sex characteristics and instead becomes a matter of self-identification. The oppressor may even benefit from a lifetime of the privilege conferred upon men through the subordination of woman and then claim womanhood. Dame Jenni Murray, presenter of BBC Woman’s Hour, came under fire for highlighting that prior to transition, transwomen benefit from the social and economic privileges accorded to men in patriarchy. Shortly afterwards, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie received backlash for differentiating between the experiences of women born as such and transwomen:

I think if you’ve lived in the world as a man, with the privileges the world accords to men, and then switch gender – it’s difficult for me to accept that then we can equate your experiences with the experiences of a woman who has lived from the beginning in the world as a woman, who has not been accorded those privileges that men are. I don’t think it’s a good thing to conflate everything into one.

If it is no longer possible to consider the experiences of those born female, to analyse the relationship between sex and socioeconomic power, feminists can no longer identify or challenge the workings of patriarchy. This is a particularly unfortunate consequence of embracing queer ideology. Women’s rights are human rights, as the slogan goes – inalienable and absolutely worth fighting for. The injustices faced by women around the globe are intolerable: one in three women will be subject to male violence within her lifetime. Yet, if the linguistic tools necessary to critique patriarchy are removed from the feminist lexicon, women’s liberation hits an insurmountable stumbling block: you cannot challenge an oppression you cannot name, after all.

The cultural significance attached to the word woman is in a state of flux. As queer politics would have it, womanhood is simply the performance of the female gender role. As radical feminism would have it, the female gender role exists purely as a sexist stereotype of woman rooted in essentialism and misogyny. The only escape queer politics offers women from patriarchal oppression is for all those who are biologically female to identify out of the category ‘woman’. To claim the label of non-binary, genderfluid, or transmasculine – anything other than a cisgender woman, who is naturally suited to her status as a second-class citizen – is the only route queer politics offers biological women to being recognised as fully human.

Women, by queer logic, cannot be self-actualised and have no meaningful inner-lives. We are simply Other to men. It is for this reason that queer ideology has been able to reduce women to “non-men” – to “pregnant people”, “uterus-havers”, and “menstruators.” It is worth asking: does trans-inclusivity depend upon women being written out of existence? While queer theory has reflected upon the nature of masculinity, it has not deconstructed the category of man beyond the point of recognition. Just as in mainstream patriarchal society, man is the normative standard of humanity and woman defined in relation to him. The positive definition of womanhood is treated as expendable within queer discourse.

As linguist Deborah Cameron asserts, women’s power to self-define is of immense political significance:

The strength of the word ‘woman’ is that it can be used to affirm our humanity, dignity and worth, without denying our embodied femaleness or treating it as a source of shame. It neither reduces us to walking wombs, nor de-sexes and disembodies us. That’s why it’s important for feminists to go on using it. A movement whose aim is to liberate women should not treat ‘woman’ as a dirty word.

However one understands the category of woman, its erasure can surely be recognised as a disastrous impediment to the liberation of women.

Lesbian Sexuality

The controversy over how womanhood is defined manifests most acutely around lesbian sexuality. An unfortunate consequence of queer politics is the problematising of homosexuality. Lesbian women and to a lesser extent gay men (for it is women’s bodies and sexual practices that are fiercely policed within patriarchy) routinely face allegations of transphobia within queer discourse. A lesbian is a woman who exclusively experiences same-sex attraction. It is the presence of female primary and secondary sex characteristics that create at least the potential for lesbian desire – gender identity is of little relevance to the parameters of same-sex attraction. As it is governed on the basis of biological sex rather than personal identification with gender, the sexuality of lesbian women is under scrutiny within queer discourse.

These words are not written with detachment. It is not an abstract concern alive only in theory. The reality is, this is a particularly uncomfortable window of time in which to be lesbian. We face mounting pressure to expand the boundaries of our sexuality until sex that involves a penis is considered a viable option. And sex that involves a penis quite simply isn’t lesbian, whether it belongs to a man or a transwoman.

I am deeply concerned by the shaming and coercion of lesbian women that now happens within queer discourse. The queer devaluation of lesbian sexuality – from the insistence that lesbians are a boring old anachronism to the pathologising of lesbian sexuality that occurs when we are branded “vagina fetishists” – is identical to the lesbophobia pedalled by social conservatives. Both the queer left and religious right go out of their way to imply something is wrong with lesbians because we desire other women.

Lesbian women are attracted by the female form. In addition to sharing a profound emotional and mental connection with other women, lesbians appreciate the female form – the beauty of women’s bodies is what sparks our desire. If biological sex ceases to be recognised as determining womanhood (or, indeed, manhood), it can no longer be said that there is such a body as a woman’s body. If the distinct set of sex characteristics which combine to form womanhood are rendered unspeakable, attraction inspired by those characteristics – lesbian desire – is made invisible. Something vital is lost when women are deprived of the language to articulate how and why we love other women (Rich, 1980).

Lesbians are being coerced back into the closet within the LGBT+ community. We receive strong encouragement to abandon the label of lesbian, which we are told is comically archaic, and embrace the umbrella term of queer in the name of inclusivity. But no sexuality is universally inclusive – by definition, sexuality is a specific set of factors which when met offer the potential for attraction. It is unreasonable – and frankly delusional – to imagine that sexuality can be stripped of any meaningful criteria.

A queer woman is less challenging to the status quo than a lesbian, easier for men to get behind, for queer is a vague term that deliberately eschews solid definitions – a queer woman may well be sexually available to men, her sexuality in no way an impediment to offering men the emotional, sexual, or reproductive labour upon which patriarchy is dependent.

Queer stigmatising of lesbians is a tactical manoeuvre designed to undermine acknowledgement of the female sex category. If there is no need to address same-sex attraction between women, the significance and permanence of sex categories demands no scrutiny. That encouraging lesbian women to consider sex that involves a penis has become newly acceptable, a legitimate line of discourse within the progressive left, is a terrible puzzle. The logic of it is straightforward enough, yet the underlying truths about what is happening within LGBT+ politics are not easy to look at. Yet still I cannot help turn it over and over in my mind, working at the ideas like a Rubik’s cube until the pieces fall into place. Queer ideology seeks to enforce compulsory heterosexuality in the lives of lesbian women just as surely as the standards set by patriarchy. By denying the possibility of lesbians exclusively loving other women, by delegitimising lesbians living woman-centric lives, queer politics undermines our liberation.

Conclusion

There is a persistent thread of misogyny running through queer politics, from the inception of queer to its present incarnation. Queer was the product of gay men’s activism, concerned primarily with sexual freedom and transgression: as such, queer did not represent the interests of lesbian women when it came into being during the 1980s and does not represent the interests of lesbian women now (Jeffreys, 2003). Queer is less about collectively challenging structural inequalities at their root than an individualised subversion of social norms.

Though it promised a radical, exciting alternative – one which many women have embraced, along with men – queer politics are ill equipped to dismantle systematic oppressions. Queer erasure of womanhood, queer disregard for women’s boundaries if they happen to be lesbian, and queer obscuring of the gender hierarchy breathes a new lease of life into patriarchy, if anything.

I dream of a world without gender. I dream of a world where men can wear dresses and be gentle without either being treated as a negation of manhood. But much more than that, I dream of a world where no assumptions are made about what it means to be woman beyond the realm of biological fact. And if that makes me a heretic in the church of gender, so be it – I’m an atheist.

Gender roles and the hierarchy they maintain are incompatible with the liberation of women and girls from patriarchal oppression. It is because I love women, and because I am a woman, that I cannot afford to pretend otherwise. Embracing gender as an identity is the equivalent of decorating the interior of a cell: it is a superficial perspective which offers no freedom.

Bibliography

Simone de Beauvoir. (1949). The Second Sex. London: Vintage

Judith Butler. (1990). Gender Trouble. London: Routledge

Andrea Dworkin. (1987). Intercourse. New York: Free Press

Marilyn French. (1986). Beyond Power: On Women, Men, and Morals. California: Ballantine Books

Sheila Jeffreys. (2003). Unpacking Queer Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press

Jack Halberstam. (1998). Female Masculinity. Carolina: Duke University Press

bell hooks. (1984). Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. London: Pluto Press

Kate Millett. (1969). Sexual Politics. Columbia: Columbia University Press

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. (2014). We Should All be Feminists. London: Fourth Estate

Adrienne Rich. (1979). On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966-1978

Adrienne Rich. (1980). Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.

Ntozake Shange. (1982). Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo. New York: Picador

Karen Tongson. (2005). Lesbian Aesthetics, Aestheticizing Lesbianism. IN Nineteenth Century Literature

Mary Wollstonecraft. (1792). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects

analysis balances out. Last week I was part of Glasgow International for After Dark, a creative conversation between LGBT artists of colour. I’d never been called an artist before, and still don’t see myself as one. Writer, yes – I feel that in my bones, and have external validation from the publishing industry. But, artist? Funnily enough, another participant questioned his own right to the label of writer because of the way Black people go largely unrecognised as ‘legitimate’ cultural critics. Or not so funny. A recurring theme, whatever the medium we worked with, was that none of us had been encouraged to think of ourselves, our work, our voices as having authority. But it was satisfying to connect, to talk about our work and the lives that inform it. Opportunities to meet other creatives who are both LGBT and people of colour are a rare, exquisite thing.

analysis balances out. Last week I was part of Glasgow International for After Dark, a creative conversation between LGBT artists of colour. I’d never been called an artist before, and still don’t see myself as one. Writer, yes – I feel that in my bones, and have external validation from the publishing industry. But, artist? Funnily enough, another participant questioned his own right to the label of writer because of the way Black people go largely unrecognised as ‘legitimate’ cultural critics. Or not so funny. A recurring theme, whatever the medium we worked with, was that none of us had been encouraged to think of ourselves, our work, our voices as having authority. But it was satisfying to connect, to talk about our work and the lives that inform it. Opportunities to meet other creatives who are both LGBT and people of colour are a rare, exquisite thing. like so many of the city’s architectural wonders, the building was funded by the labour of enslaved Black people. Growing up amidst the tensions created by that repressed history, it was impossible for me to develop a sense of belonging. When Blackness and Scottishness are often treated as two mutually exclusive identities (a seemingly endless number of white Scots can’t get their head around Black people being born ‘here’, raised ‘here’, from ‘here’), how could it be otherwise? It felt powerful to sit and talk and eat and drink in the Gallery, to claim a space that was never meant for us.

like so many of the city’s architectural wonders, the building was funded by the labour of enslaved Black people. Growing up amidst the tensions created by that repressed history, it was impossible for me to develop a sense of belonging. When Blackness and Scottishness are often treated as two mutually exclusive identities (a seemingly endless number of white Scots can’t get their head around Black people being born ‘here’, raised ‘here’, from ‘here’), how could it be otherwise? It felt powerful to sit and talk and eat and drink in the Gallery, to claim a space that was never meant for us. We get to know each other over pizza (which should be mandatory in every green room), sharing bits of our lives without glossing over trauma. So much is possible when women come together and talk openly about violence. When you have the support of feminist women, and are free from the worry of whether your disclosure will be shamed or disbelieved, it is much easier to get to the root of how and why violence against women happens. There is also a lot of joy in those connections.

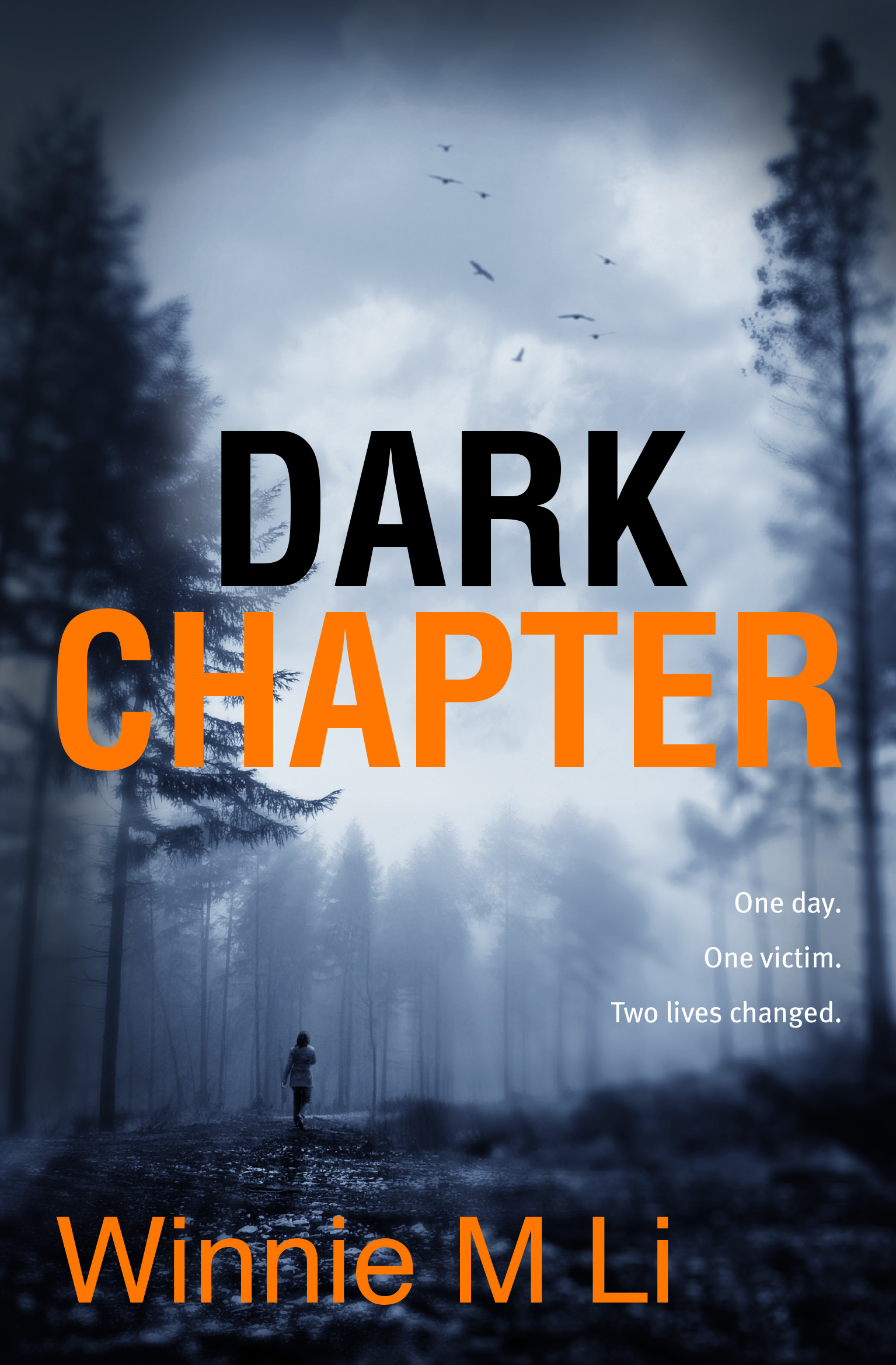

We get to know each other over pizza (which should be mandatory in every green room), sharing bits of our lives without glossing over trauma. So much is possible when women come together and talk openly about violence. When you have the support of feminist women, and are free from the worry of whether your disclosure will be shamed or disbelieved, it is much easier to get to the root of how and why violence against women happens. There is also a lot of joy in those connections. Winnie reveals that she loved writing as a child, but never anticipated that her first book – Dark Chapter – would be based on the story of her own rape. The perpetrator left her with 39 separate injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder. Winnie quit her job, went about the business of putting herself back together, and rebuilt her life. Her writing perfectly captures the reality of experiencing sexual violence. In an

Winnie reveals that she loved writing as a child, but never anticipated that her first book – Dark Chapter – would be based on the story of her own rape. The perpetrator left her with 39 separate injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder. Winnie quit her job, went about the business of putting herself back together, and rebuilt her life. Her writing perfectly captures the reality of experiencing sexual violence. In an  room.” A procedure that took 45 minutes would have repercussions for the rest of her life. Hibo underwent type three FGM, which she wrote about in her memoir Cut. Of this experience, Hibo says “you don’t heal from it, you learn to cope with it.” During her work in schools, Hibo was compelled to start challenging FGM when she realised young girls were at risk. Explaining her advocacy, Hibo says “I used my trauma as a tool for education.” Her work has changed how the education system, the British government, and even the FBI approach the issue of FGM. Hibo is proud of how attitudes have begun to shift against FGM in recent years, a change to which her work has greatly contributed, but is adamant there’s still a long way to go before this particular battle is won. Every 11 seconds a girl is cut. FGM has been illegal in Britain since 1985, but nobody has yet been prosecuted for carrying the procedure out on a girl.

room.” A procedure that took 45 minutes would have repercussions for the rest of her life. Hibo underwent type three FGM, which she wrote about in her memoir Cut. Of this experience, Hibo says “you don’t heal from it, you learn to cope with it.” During her work in schools, Hibo was compelled to start challenging FGM when she realised young girls were at risk. Explaining her advocacy, Hibo says “I used my trauma as a tool for education.” Her work has changed how the education system, the British government, and even the FBI approach the issue of FGM. Hibo is proud of how attitudes have begun to shift against FGM in recent years, a change to which her work has greatly contributed, but is adamant there’s still a long way to go before this particular battle is won. Every 11 seconds a girl is cut. FGM has been illegal in Britain since 1985, but nobody has yet been prosecuted for carrying the procedure out on a girl. Next it’s my turn to speak. I have boundless respect for the other women on this panel and feel honoured to sit alongside them. Yet there are no pangs of imposter syndrome, which is another recent positive step. I tell the audience about the context that shaped my work, the isolation of growing up Black in Scotland, the ways in which gas-lighting is used to cover up racism – which the country has long since struggled to acknowledge as a social, political reality. It’s easy enough: there’s no scarcity of women of colour in the room. I talk about the importance of having found feminist community in digital spaces; that it felt natural to raise a dissenting voice online in a way that it didn’t in person, offline. I share my motivation in creating a learning resource for women trying to engage with feminist politics, how it’s done with the goal of helping build a truly anti-racist feminist movement that really is committed to the liberation of all women. And then I turn to Vanessa.

Next it’s my turn to speak. I have boundless respect for the other women on this panel and feel honoured to sit alongside them. Yet there are no pangs of imposter syndrome, which is another recent positive step. I tell the audience about the context that shaped my work, the isolation of growing up Black in Scotland, the ways in which gas-lighting is used to cover up racism – which the country has long since struggled to acknowledge as a social, political reality. It’s easy enough: there’s no scarcity of women of colour in the room. I talk about the importance of having found feminist community in digital spaces; that it felt natural to raise a dissenting voice online in a way that it didn’t in person, offline. I share my motivation in creating a learning resource for women trying to engage with feminist politics, how it’s done with the goal of helping build a truly anti-racist feminist movement that really is committed to the liberation of all women. And then I turn to Vanessa. sphere.” Before having children she was a barrister, which shows in how she forms an argument. As a new mother, no longer practicing her profession, she was conscious that “my political power was gone, my economic power was gone, my body had changed.” She struggled against the idea mothers are not political, a misconception “which Mumsnet prove wrong.” To Vanessa there is no doubt that women’s bodies exist as the site of oppression in patriarchal society. She calls for an embodied feminist politics that recognise the significance of sex in determining how we experience the world. Vanessa points out that boys begin assaulting girls from a young age, highlighting the patterns of violence that emerge through gendered socialisation.

sphere.” Before having children she was a barrister, which shows in how she forms an argument. As a new mother, no longer practicing her profession, she was conscious that “my political power was gone, my economic power was gone, my body had changed.” She struggled against the idea mothers are not political, a misconception “which Mumsnet prove wrong.” To Vanessa there is no doubt that women’s bodies exist as the site of oppression in patriarchal society. She calls for an embodied feminist politics that recognise the significance of sex in determining how we experience the world. Vanessa points out that boys begin assaulting girls from a young age, highlighting the patterns of violence that emerge through gendered socialisation.

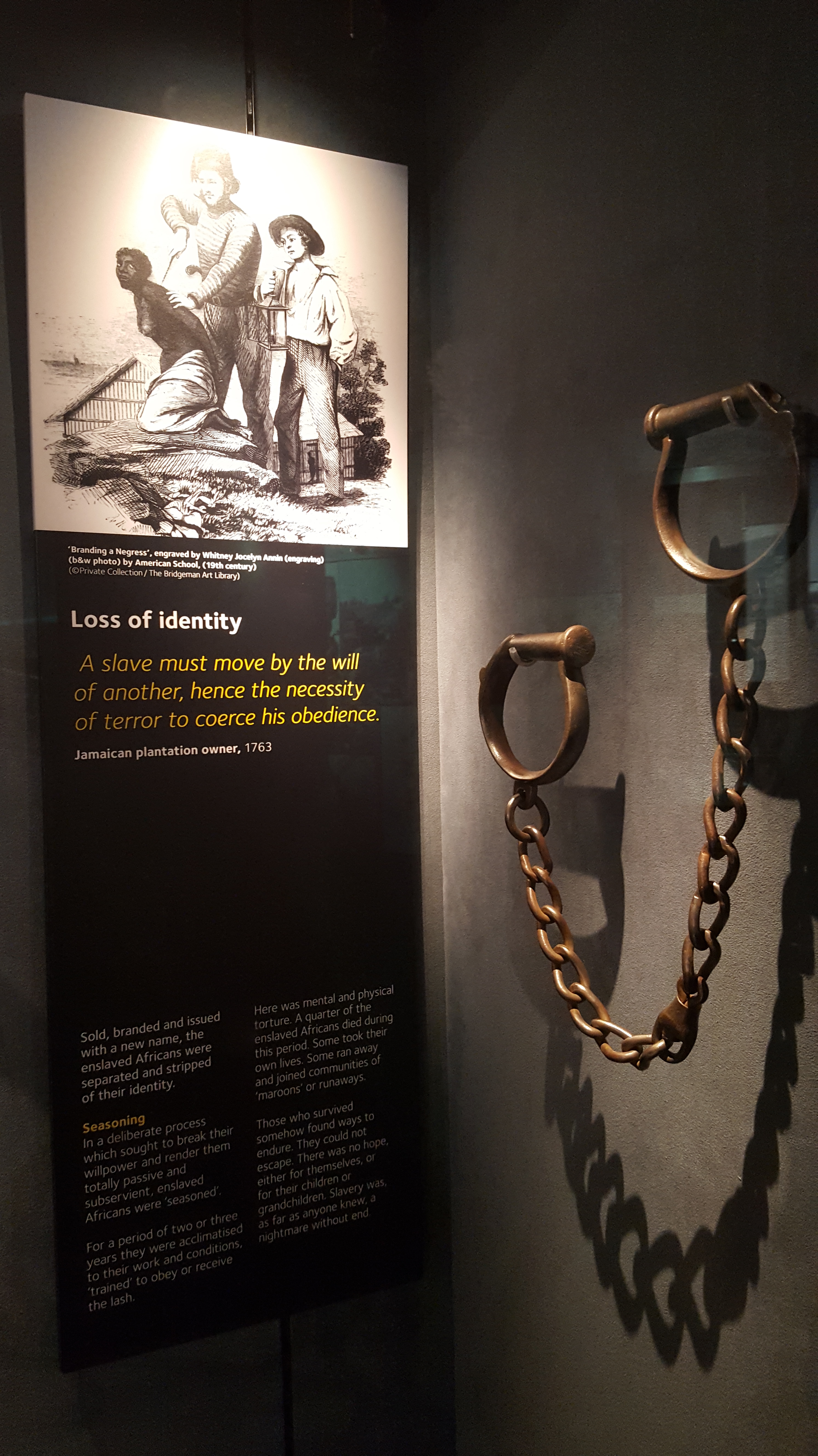

I walk to the International Slavery Museum, taking in Liverpool as I go. The architecture is striking against the blue sky, and cherry blossoms line a walkway towards the dock. It’s a beautiful city in spring. There are a number of art spaces and cafés I could happily delve into but this mission, I feel, is important. So many of Scotland’s ongoing problems with racism are rooted in an unwillingness to examine the country’s history with race, a refusal to acknowledge how that past shaped the present reality. Earlier this year I visited Berlin, and there are public monuments to the victims of World War 2 placed throughout the city. Each monument included explanations of how and why these people died, giving history to provide context. It was deeply emotional, but there was something healing in giving public space over to recognising those atrocities. Repressing a history only adds to the trauma – which is why I am determined to visit the Slavery Museum.

I walk to the International Slavery Museum, taking in Liverpool as I go. The architecture is striking against the blue sky, and cherry blossoms line a walkway towards the dock. It’s a beautiful city in spring. There are a number of art spaces and cafés I could happily delve into but this mission, I feel, is important. So many of Scotland’s ongoing problems with racism are rooted in an unwillingness to examine the country’s history with race, a refusal to acknowledge how that past shaped the present reality. Earlier this year I visited Berlin, and there are public monuments to the victims of World War 2 placed throughout the city. Each monument included explanations of how and why these people died, giving history to provide context. It was deeply emotional, but there was something healing in giving public space over to recognising those atrocities. Repressing a history only adds to the trauma – which is why I am determined to visit the Slavery Museum. and its legacies”, exploring not only the past but how it has informed life in modern day Britain. Beside the entrance is an invitation for people to write about the thoughts and feelings evoked, and stick their postcard on a wall. I like that people are given the space and encouragement needed to try and grapple with the painful knowledge held here. The realities of the slave trade were horrifying. Black people were beaten and raped and killed and worked to death for the profit of white people. Denying it doesn’t help the African people who were forcibly removed from their homes, and it doesn’t help anybody now either.

and its legacies”, exploring not only the past but how it has informed life in modern day Britain. Beside the entrance is an invitation for people to write about the thoughts and feelings evoked, and stick their postcard on a wall. I like that people are given the space and encouragement needed to try and grapple with the painful knowledge held here. The realities of the slave trade were horrifying. Black people were beaten and raped and killed and worked to death for the profit of white people. Denying it doesn’t help the African people who were forcibly removed from their homes, and it doesn’t help anybody now either.

though what one group values about my feminism is a point of contention for the other. In the eyes of a number of straight Black women in my life, I am too radical – my unwillingness to divorce gendered aspects of the personal from the political creates a rift. With some of the white lesbians in my life, I am insufficiently radical – too invested in exploring grey areas and the pesky politics of race to fit with their understanding of lesbian feminism.

though what one group values about my feminism is a point of contention for the other. In the eyes of a number of straight Black women in my life, I am too radical – my unwillingness to divorce gendered aspects of the personal from the political creates a rift. With some of the white lesbians in my life, I am insufficiently radical – too invested in exploring grey areas and the pesky politics of race to fit with their understanding of lesbian feminism. unhindered by the tensions of today. Where there’s common ground, there would be room for coalition. Where there’s

unhindered by the tensions of today. Where there’s common ground, there would be room for coalition. Where there’s

sexuality and “TERF” politics, including such dubious pearls of wisdom such as this: “repeated use of the word ‘lesbian’ is also a dog whistle for TERFs.” If even saying lesbian can be taken as proof of transphobia, something has clearly gone wrong in this conversation. As Black feminist theory has long held (Hill Collins, 1990), self-definition is an essential step in the liberation of any oppressed group – including lesbians. And yet straight feminists are often willing to be complicit in lesbian erasure or, worse still, deny that erasure is happening even as lesbians challenge it.

sexuality and “TERF” politics, including such dubious pearls of wisdom such as this: “repeated use of the word ‘lesbian’ is also a dog whistle for TERFs.” If even saying lesbian can be taken as proof of transphobia, something has clearly gone wrong in this conversation. As Black feminist theory has long held (Hill Collins, 1990), self-definition is an essential step in the liberation of any oppressed group – including lesbians. And yet straight feminists are often willing to be complicit in lesbian erasure or, worse still, deny that erasure is happening even as lesbians challenge it.

Gender is een hiërarchie die het mogelijk maakt voor mannen om dominant te zijn en creëert de condities voor de ondergeschikte positie van vrouwen. Omdat gender een fundamenteel onderdeel is van de witte, kapitalistische samenleving (Hooks, 1984), is het is bijzonder ontzettend om te constateren dat elementen van het ’queer discours’ beweren dat gender niet alleen in het aangeboren en onveranderlijk, maar zelfs heilig is.

Gender is een hiërarchie die het mogelijk maakt voor mannen om dominant te zijn en creëert de condities voor de ondergeschikte positie van vrouwen. Omdat gender een fundamenteel onderdeel is van de witte, kapitalistische samenleving (Hooks, 1984), is het is bijzonder ontzettend om te constateren dat elementen van het ’queer discours’ beweren dat gender niet alleen in het aangeboren en onveranderlijk, maar zelfs heilig is. opvatting van gender als een kwestie van performativiteit of persoonlijke identificatie ontkent haar praktische functie in een hiërarchie. Elke ideologie die gender niet als een manier van onderdrukking van vrouwen onderscheidt, kan niet als feministisch worden omschreven – inderdaad, aangezien queer ideologie grotendeels onkritisch blijft ten opzicht van machtsverschillen achter de seksuele politiek, is anti-vrouw.

opvatting van gender als een kwestie van performativiteit of persoonlijke identificatie ontkent haar praktische functie in een hiërarchie. Elke ideologie die gender niet als een manier van onderdrukking van vrouwen onderscheidt, kan niet als feministisch worden omschreven – inderdaad, aangezien queer ideologie grotendeels onkritisch blijft ten opzicht van machtsverschillen achter de seksuele politiek, is anti-vrouw.

van de LGBT + alfabet soep, ligt er altijd al homofobie aan de basis van queer politiek. Queer-ideologie kwam op in reactie op lesbische feministische principes, die een radicale maatschappelijke verandering bepleiten door het transformeren van persoonlijke levens (Jeffreys, 2003). De politieke belangen van lesbische vrouwen en gemarginaliseerde homoseksuele mannen – met name de afschaffing van geslachtsrollen – worden door queer politiek van tafel geveegd. Individualisme voorkomt elke geconcentreerde focus op feministische en homoseksuele bevrijdingspolitiek, wat door queer discours wordt beschreven als ’ouderwets’, ’saai’ of ’anti-seks’.

van de LGBT + alfabet soep, ligt er altijd al homofobie aan de basis van queer politiek. Queer-ideologie kwam op in reactie op lesbische feministische principes, die een radicale maatschappelijke verandering bepleiten door het transformeren van persoonlijke levens (Jeffreys, 2003). De politieke belangen van lesbische vrouwen en gemarginaliseerde homoseksuele mannen – met name de afschaffing van geslachtsrollen – worden door queer politiek van tafel geveegd. Individualisme voorkomt elke geconcentreerde focus op feministische en homoseksuele bevrijdingspolitiek, wat door queer discours wordt beschreven als ’ouderwets’, ’saai’ of ’anti-seks’. En zo worden de feministen die gender-ideologie bevragen als onverdraagzaam gebrandmerkt, de kritiek en die vrouwen die dapper genoeg zijn om deze te maken, worden als illegitiem weg gezet. Vrouwen die genderideologie in vraag stellen, worden TERF’s genoemd – we worden er telkens verteld dat hun enige motief voor hun kritiek op genderideologie valsheid is, in tegenstelling tot een betekenisvolle zorg voor het welzijn van vrouwen en meisjes. Daarmee citeer ik Mary Shelley: “Pas op; want ik ben onbevreesd en daarom krachtig.” Elke poging om vrouwen te ontmoedigen om onze onderdrukking aan te pakken, is diep verdacht.

En zo worden de feministen die gender-ideologie bevragen als onverdraagzaam gebrandmerkt, de kritiek en die vrouwen die dapper genoeg zijn om deze te maken, worden als illegitiem weg gezet. Vrouwen die genderideologie in vraag stellen, worden TERF’s genoemd – we worden er telkens verteld dat hun enige motief voor hun kritiek op genderideologie valsheid is, in tegenstelling tot een betekenisvolle zorg voor het welzijn van vrouwen en meisjes. Daarmee citeer ik Mary Shelley: “Pas op; want ik ben onbevreesd en daarom krachtig.” Elke poging om vrouwen te ontmoedigen om onze onderdrukking aan te pakken, is diep verdacht.

Malgré tout ce qui se dit sur une « communauté queer », alliance prétendue entre les personnes LGBT +, l’homophobie a toujours été centrale à la politique queer. En effet, l’idéologie queer a émergé comme mouvement de ressac opposé aux principes féministes lesbiens, qui préconisaient un changement social radical par la transformation des vies individuelles (Jeffreys, 2003). Les intérêts politiques des femmes lesbiennes et des hommes gais marginalisés, à commencer par l’abolition des rôles de genre, ont été rejetés dans les milieux queer. L’individualisme interdisait tout accent particulier sur les politiques de libération féministe et gay, que le discours queer commença à décrire comme démodées, ternes ou anti-sexe.

Malgré tout ce qui se dit sur une « communauté queer », alliance prétendue entre les personnes LGBT +, l’homophobie a toujours été centrale à la politique queer. En effet, l’idéologie queer a émergé comme mouvement de ressac opposé aux principes féministes lesbiens, qui préconisaient un changement social radical par la transformation des vies individuelles (Jeffreys, 2003). Les intérêts politiques des femmes lesbiennes et des hommes gais marginalisés, à commencer par l’abolition des rôles de genre, ont été rejetés dans les milieux queer. L’individualisme interdisait tout accent particulier sur les politiques de libération féministe et gay, que le discours queer commença à décrire comme démodées, ternes ou anti-sexe.

votre sexualité sera déconstruite implacablement parce que soupçonnée de faire preuve d’ »exclusion ». Comme je l’ai écrit dans un

votre sexualité sera déconstruite implacablement parce que soupçonnée de faire preuve d’ »exclusion ». Comme je l’ai écrit dans un

On our way out this afternoon, she gently pointed out that I seemed a bit down. My depression has been severe this year, and I know Nana worries. At first I didn’t say much. But months of therapy have made it substantially easier to divine the root cause of a problem. I told her that a

On our way out this afternoon, she gently pointed out that I seemed a bit down. My depression has been severe this year, and I know Nana worries. At first I didn’t say much. But months of therapy have made it substantially easier to divine the root cause of a problem. I told her that a

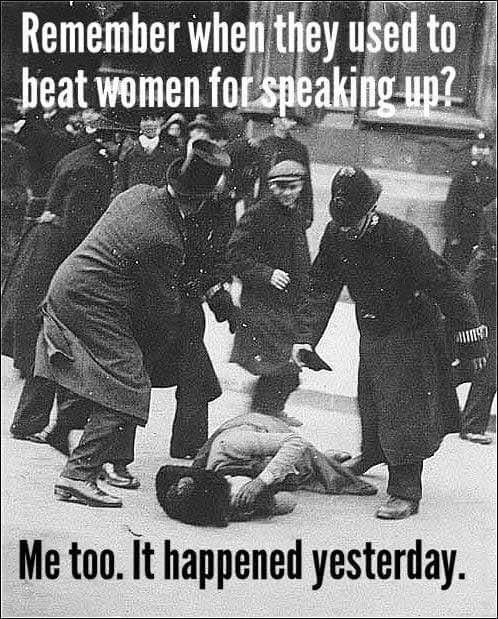

opens the latest chapter of a story called patriarchy. Both the violence and the context that enabled it to happen must be scrutinised.

opens the latest chapter of a story called patriarchy. Both the violence and the context that enabled it to happen must be scrutinised.

There must be a way to talk about the tensions between gender ideology and sexual politics without abusive language or acts of violence. The subject is fraught, uncomfortable, and certainly not abstract for anyone involved with gender discourse – which is all the more reason to bring empathy to the table. Dehumanising women to the point where we are considered legitimate targets of violence only upholds the values set by patriarchy. We do not approach the subject of gender from a position of power – gender has been used, for hundreds upon hundreds of years, to oppress women. That gender is fundamental to the oppression of women is too often overlooked in gender discourse.

There must be a way to talk about the tensions between gender ideology and sexual politics without abusive language or acts of violence. The subject is fraught, uncomfortable, and certainly not abstract for anyone involved with gender discourse – which is all the more reason to bring empathy to the table. Dehumanising women to the point where we are considered legitimate targets of violence only upholds the values set by patriarchy. We do not approach the subject of gender from a position of power – gender has been used, for hundreds upon hundreds of years, to oppress women. That gender is fundamental to the oppression of women is too often overlooked in gender discourse. assault to keep your ally cookies on queer identity politics, you’re complicit. If you give language that normalises violence against women, you’re complicit. Violence against women has no place in any context. That is what radical feminists consistently argue. Radical feminist women are depicted as violent simply for our ideas about gender – meanwhile, those who perpetrate physical acts of violence against women are framed as our victims.

assault to keep your ally cookies on queer identity politics, you’re complicit. If you give language that normalises violence against women, you’re complicit. Violence against women has no place in any context. That is what radical feminists consistently argue. Radical feminist women are depicted as violent simply for our ideas about gender – meanwhile, those who perpetrate physical acts of violence against women are framed as our victims.