A brief foreword: this is my account of attending Young Feminist Summer School in Brussels from the 7-11th of September, 2016. My place was very kindly sponsored by Engender. Text originally posted here, on the European Women’s Lobby site.

Before

My name is Claire. I am a feminist – specifically, a feminist of the Black and radical variety. I live in Scotland, where I’ve had the privilege of volunteering with the Glasgow Women’s Library for almost two years, and blog as Sister Outrider. In the year since I started blogging, I’ve written about intersectionality, how race operates as a dynamic, racism in the feminist movement, and white privilege. In addition, I run feminist workshops and speak about Black feminism at events; although writing has been crucial to me finding voice as a feminist, my priority is improving life for other women – women of colour in particular – and that requires deeds as well as words. So I applied to AGORA ’16 Young Feminist Summer School in order to learn more about how to bridge the gap between feminist theory and practice, between ideas and reality.

Feminist Summer School. Those three words promised everything about which I am passionate: learning, feminist politics, and an opportunity to work with brilliant women. Fifty places were open to young women from all across Europe, inviting us to Brussels for five days to learn how best our activism can bring about change. One of those places is mine. Young Feminist Summer School was organised by the European Women’s Lobby, the largest network of women’s organisations in the whole of the EU. Having read about the extraordinary achievements of my fellow attendees, the strength of their commitment to women’s liberation, it is clear that this project has so much valuable knowledge to offer about feminist campaigning, organisation, and projects.

It still doesn’t feel real. My plane tickets are booked, the boarding passes printed, and yet I can’t quite believe that I’m going to Brussels in September. I applied to AGORA ’16 at the beginning of the year – the deadline fell on the same day as my university required applications for PhD research proposals to be submitted and coincided with the funding application, too. Although things got a bit hectic (translation: staring at the computer screen and questioning the meaning of life, the wisdom of my professional choices), this turned out to be a bit of a blessing in disguise because, being so very stressed about my future, it didn’t occur to me to be nervous about whether or not I’d be accepted into Young Feminist Summer School. I had simply thought, best case scenario, AGORA ’16 would be a nice way to spend the time between finishing the dissertation for my MLitt in Gender Studies and starting my research degree. And it will be.

Confession time: my application was totally last minute. I sent the email within a half hour of the deadline, indecisive until the eleventh hour. This is because I wasn’t sure that I’d have enough to offer the programme to be a deserving candidate. Silly, in retrospect – there’s nothing to lose by applying. And yet… Young Feminist Summer School had been popping up on my Twitter feed for weeks, being shared again and again by women I respect both in a sisterly and professional capacity. It looked so wonderful – a way to develop feminist praxis, meet and learn from young women all around Europe, and go to Brussels, a place which I had never visited before.

One of my fellow Glasgow Women’s Library Volunteers, Louisina, talked so enthusiastically about how much her daughter had enjoyed and gained from attending the first Young Feminist Summer School in 2015. Feminist Summer School looked so brilliant that it became almost intimidating. Was I good enough, accomplished enough, to apply? And then I thought about how much impostor syndrome holds women back. I asked myself whether a straight white man with my skills, experience, and enthusiasm would ever question his right to such an opportunity. The answer: don’t be ridiculous! And so I send the form.

Full credit for this budding confidence goes to Glasgow Women’s Library. Spend enough time in women’s spaces, and you start to believe that anything is possible. All of the qualities other women see in you grow slowly visible to your own eyes, shape your self-perception, and gradually eclipse self-doubt. Through recognising the talents of other women, your own as you become part of the team, you subconsciously begin to unpick the layers of misogyny that were hidden away in the depths of your mind and develop a justifiable faith in your own capabilities.

My feminist praxis is intersectional, which means that I consider hierarchies like race and class alongside gender in my analysis of power structures and approach to feminism. In the run up to Young Feminist Summer School I have also been wondering how, as a Black feminist, I would fit in a European context. Here in Scotland, in Britain, it can be something of a struggle getting people to think about racism in the same way they think about sexism, to acknowledge that the two are connected. There persists an idea that race matters less than sex in determining women’s experiences, a perspective which completely overlooks the realities faced by women of colour. How that conversation generally unfolds in other parts of Europe, it is impossible to guess – I am very much looking forward to finding out, to hearing from women whose experiences are different to my own.

There is no way to know what a project as new as Young Feminist Summer School is going to be like, to predict how I will find being in a new place and meeting so many new people. But all of those possibilities are exciting. I am proud to be going, and delighted that this year my home country Scotland is represented by two women of colour. It is the ambition of the European Women’s Lobby’s vision for building a better future, the creativity of their approach in bringing young feminists together to learn from each other, that make Young Feminist Summer School such a thrilling prospect. I look forward to AGORA ’16, and to everything that will follow in the work of my fellow participants.

During, Part 1

I am not anxious about Young Feminist Summer School. Throughout the journey from my quiet coastal hometown to Glasgow, from Glasgow’s familiar buzz to the remote beauty of Edinburgh, I am free from the acute panic that typically plagues any journey to an unknown destination. In both a direct and philosophical way, this novel peace of mind is due to my enthusiasm for ideas, for translating feminist theory into practice. The night before AGORA I was on the phone with a friend, and we stayed up until about 3.30 in the morning talking about the tension between identity politics and structural analysis in the politics of liberation. It was one of those intricate, intense conversations to which a good night’s sleep is sacrificed without a second thought. Now, some 12 hours later and thousands of feet above the earth’s surface, I am physically too tired to experience anxiety. (Note to self: experiment with sleep deprivation before all significant undertakings…) At AGORA ’16, I expect to meet like-minded women. Though we have never met, I anticipate finding a similar passion in my fellow feminists.

Here in Brussels, on my first trip abroad in the capacity of feminist, I begin to think about national identity. Walking through passport control, I froze for a moment, uncertain of whether I could still queue as an EU citizen in the wake of Britain’s referendum, until Nadine told me it was valid for another 2 years. The practical implications of Britain leaving the European Union are still emerging, an endless string of unfortunate consequences. When the time eventually comes to change my passport, I wonder what will replace it. A woman after my own heart, Nadine has also suggested we Tweet our First Minister Nicola Sturgeon a selfie of the AGORA ’16 Scottish contingent. I like this idea. After the Black woman who ran the Ireland Twitter account for a week was sent torrents of racist abuse (as in the UK, Black can only ever be safe if it is considered other to the ’’us’’ who belong and make up the fabric of society), it feels important to show how proudly two women of colour are representing Scotland.

The air-conditioned bus into the city, with its tinted windows, is cool and quiet, allowing for introspection. I am a Scottish feminist. I am a Black woman. Here, in a different context, it’s a fresh opportunity to consider how those things fit together. I flew here with two women also involved in Scottish feminist organisations, and I myself am part of Glasgow Women’s Library. The three of us have worked together before. For the first time, I see how I fit into the nexus of Scottish feminism – rather than trying to define myself, my work, against it, I see now that they fit under the umbrella of Scottish feminism.

It can be disproportionately white, back home. Whenever I go to feminist events, I am consciously looking for women of colour. Are we a part of the audience? Are we represented on the panels? Are women of colour involved behind the scenes in feminist organising? If a feminist space or event is entirely white, it is quite simple: I do not belong in that context. No feminist setting that does not value and listen to what women of colour have to say is relevant to me – how can anyone fit into a group where they are ignored, made irrelevant as Other? In Scotland it feels like something is changing for the better. Our new Poet Makar, Jackie Kay, is a Black lesbian woman. At GWL we have established Collect:If, a network run by and for creative women of colour. Dr Akwugo Emejulu convened the Women of Colour in Europe conference in Edinburgh last weekend, highlighting the academic and creative contributions of voices marginalised altogether too often. That same weekend Lux screened a documentary about Audre Lorde, The Berlin Years, at Glasgow Film Theatre and it sold out – people cared about Lorde’s life, her significance. All these things give me place, knit me a little closer into Scottish feminism.

From bus to train, we venture into Brussels. I take a particular delight in asking for ’’un voyage, s’il vous plait’’. The ticket is quite different from those in Scotland. Trundling my case behind me, I am an obvious tourist. Upon getting stuck in the accessible ticket barrier, I envision spending the rest of my life in that perspex box before managing to escape. Emerging from the metro is like stepping into another world – so different to my native Scotland. The sky is blue, the streets cobbled, and the architecture distinctly European. On our way to the Mayoral reception there is so much to feast our eyes on, and the scent of freshly cooked waffles is near-impossible to resist, but it is well worth it upon arrival.

The town hall is exquisite. It looks more like the Vatican than a municipal building, and I am in awe. Upon entering the reception, I am given a cool glass of champagne – so refreshing after a long day. It is significant, I think, that among the first to approach me and introduce themselves of the Summer School attendees are my fellow Black women. This recognition is so welcome – being in a totally unfamiliar environment can get unsettling. Without preamble, we delve into a fascinating conversation: the state of the UK Labour party, Black identity across the diaspora, how “diversity” only extends so high in organisations, the ways in which Black women do and do not relate to one another… It’s exhilarating.

The achievements of these women are extraordinary, and it is a privilege to be among them, energised by their enthusiasm and the breadth of their vision for engineering social change. This conversation, under the fresco decorating the town hall ceiling, is all that I had been hoping for and more. Everything that I have planned with my own work seems possible – a very promising start to Young Feminist Summer School. We head back to the hostel, buoyed by so much feminist company as we traverse the streets of Brussels. Later that evening, as my roommate curls up in bed reading Patricia Hill Collins, I realise AGORA ’16 is exactly where I am meant to be.

During, Part 2

Feminist Summer School exceeds my every expectation. Our first session sets the tone for everything that follows, establishing our core values: to speak with intention, to listen with attention, and be mindful of the group. As we share collective responsibility for the conversation and how it impacts on our fellow participants, everyone tries to be particularly conscious of the needs of others – an early lesson on how to successfully translate feminist principle into practice, the value of which becomes apparent as the day continues. This element of care enables honest and open discussion, and truly creative thought flourishes. Critics of safe spaces perhaps do not always see how, in certain circumstances, they enable rather than hinder discussion. And there is no end of challenge to our opinions, even those closely held – as one participant observes, “there are many feminisms here, not one feminism.”

We are all curious about our sisters: where their experiences match our own and where their experiences are different. Our contexts are diverse in this group – 49 women representing 22 countries – and there are factors of race, disability, sexuality, class, faith, language, etc. shaping our individual lived experiences in a vast number of ways, so that curiosity is pressing.

There are many shared concerns, particularly the malaise that sets in with the popular misconception that we have achieved equality now, that we don’t really need feminism any more, a falsehood that enables the erosion of advancements that have already been made towards equality. This perception that equality exists erases ongoing social inequalities. The rise of fascism in Europe, of right-wing politicians propagating misogyny, racism, homophobia, classism, and anti-immigration rhetoric is also causing a palpable worry that transcends borders. We discuss how austerity disproportionately impacts women, the intersection of disability and gender politics that is overlooked in so much of the feminist movement, and how in conservative countries – even in Romania, where the procedure is legal – abortion and other aspects of reproductive healthcare are made so difficult to access.

During the lunch break, these conversations continue at an informal level, women seeking out women whose perspective has resonated with them or overlaps with their own cause. I step into a discussion about the politics of Black women’s hair – how wearing it natural creates assumptions of radical politics in the vein of Malcolm X, and relaxing results in a whole host of assumptions about the politics of respectability. Through the conversation, parallels are drawn between the warped perceptions connecting Black women’s hair with our politics and the similar implications projected onto hijabi women.

During the afternoon sessions there are three workshops to choose from, two of which we can attend, offering real insight into the European Women’s Lobby’s campaigning. The first I attend is Whose Choice? A workshop on prostitution, the sex industry, and why the European Women’s Lobby endorses the Nordic Model, which is to criminalise purchasing sex (almost always done by men), not selling sex (almost always done by women) with a view to ending demand. This subject is particularly contentious in the feminist movement, with a divide between those who focus on the significance of individual choice and those who consider the context in which choice is made. Pierrette, our facilitator, creates an environment that is conducive to respectful discussion – as a result, we feel unafraid to share our perspectives, even when they are contradictory at points. It is a constructive way to learn from one another. With umbrella organisations it can sometimes be difficult to pinpoint a specific set of beliefs, and I gain a new respect for the European Women’s Lobby because they have a clear set of principles through which prostitution is acknowledged as a form of male violence against women in their analysis and campaigning.

Then we move on to Yes Means Yes, a workshop on sex education and consent. The European Women’s Lobby are starting a project to promote healthy attitudes towards sexuality. It is an area about which most of us are passionate and Nadine, my fellow Scottish candidate, does this professionally. As always, the quality and the depth of knowledge in the room is impressive. This makes me hopeful: it is only through education that we can change attitudes towards sex, consent, and subsequently behaviour. As many as three million women and girls are victims of sexual assault or other forms of male violence against women. It is endemic. But we have the ability to change that.

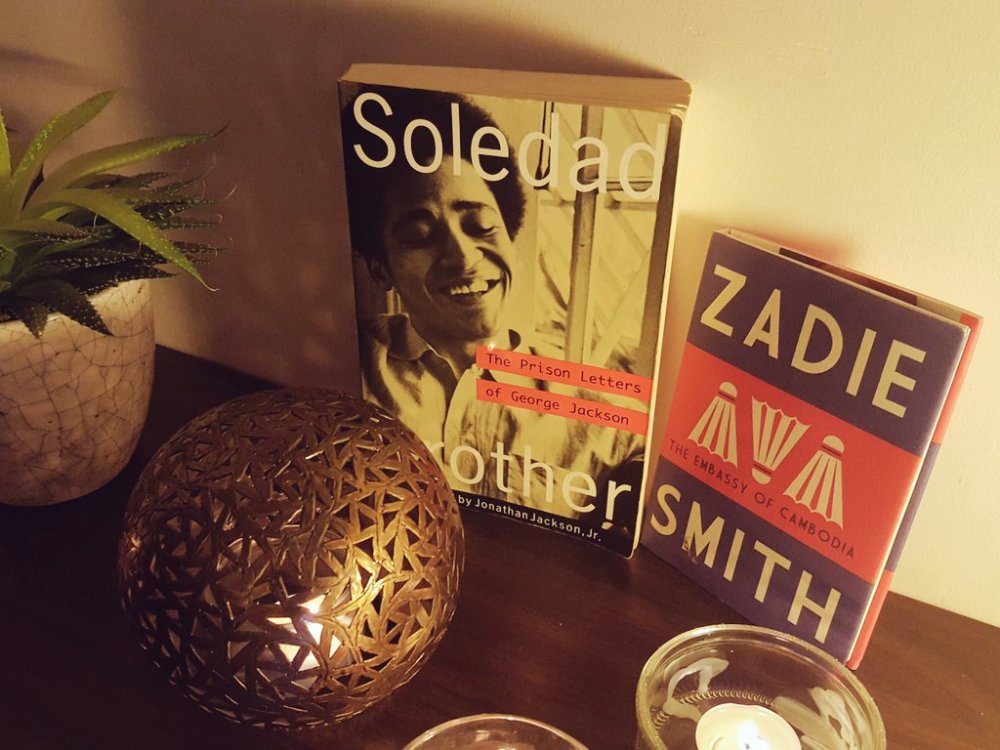

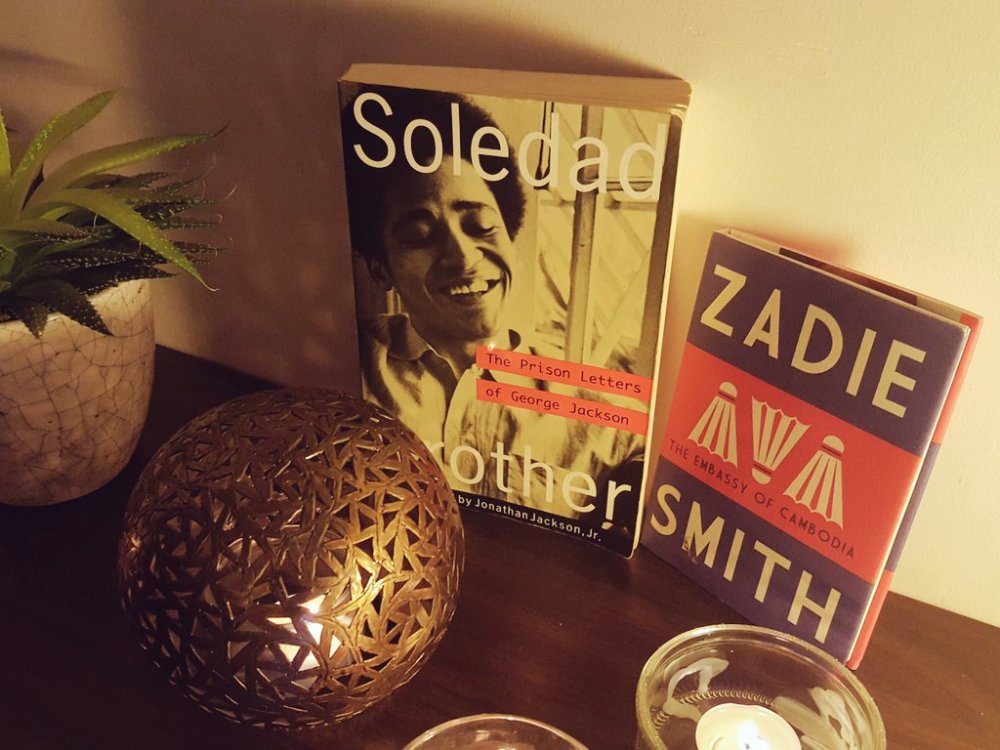

Every moment filled with learning, Young Feminist Summer School is an exciting experience – but it is also tiring. So we go out into the city to unwind during the welcome party and get a sense of Brussels. It is a beautiful city, though I will never get used to the traffic. Despite the chaos of the roads, there is something fundamentally peaceful about Brussels. The balconies and bridges are so very picturesque, the architecture distinctly European. Yet, in some ways, Brussels is reminiscent of my home city: Glasgow. It has a friendly atmosphere. Le Space confirms that initial perception. There is wine and good food. On the bookshelves, I find George Jackson’s prison letters and pour over his words to Angela Davis. One of Zadie Smith’s less known short stories, The Embassy of Cambodia, sits between volumes of French literature. This is my type of bar.

All the same, it has been a very long day. And I am still hungry. Three of us slip out in search of that renowned Belgian cuisine: chips. Becca is the strategist, orchestrating a methodical sweep of these unfamiliar streets. It is not long until we are rewarded. The chips are hot, delicious, and melt in the mouth. Bliss for three euros. It is no disrespect to AGORA ’16 that I consider this moment one of the highlights of my trip. When we return to the bar, someone has added chalk art to the walls. “Feminisme et Frites” – the perfect combination.

During, Part 3

Visiting the European Parliament is one of the highlights of Young Feminist Summer School. Despite having been up late the night before for the party, there is a buzz about the group that carries me through the tiredness. We get up early for breakfast, double check that we have our passports, and it is time to go. The parliament building is visually stunning, a modern fusion of glass and chrome. All the flags on display, the variety of languages on every sign, convey a politics of unity and consensus that resonate with me, reflect the purpose behind the AGORA ’16 group.

Ahinara, one of the Young Feminist Summer School attendees, delivers a talk on the European Union’s significance to her, describing her time writing about the institution as a journalist and then interning from the EU upon realising its power for enacting social change. Her enthusiasm and knowledge chipped away some of the mistrust I feel towards large bodies of government. As Audre Lorde said, “the master’s tools can never dismantle the master’s house” – in broad terms, my view was that the state existed as a fundamentally patriarchal and colonial institution and, as such, was fundamentally an oppressive structure. But the words of another attendee have been playing over in my mind concerning the European Union: “government has the power to liberate as well as oppress.” We learn from each other constantly during AGORA.

The next session is inspirational. Malin Bjork and Soraya Post, two MEPs active on the femme committee, come and speak to us. That the Young Feminist Summer School is worth fitting into their busy schedules is striking: I feel aware that not only of our existing achievements, but our potential for enacting change in the future, give us real significance as a group. Hearing Malin and Soraya discuss their politics and careers is uplifting, as their careers make clear that driving meaningful social change can be possible. Soraya’s words in particular chime with me: she is the first Roma woman to be elected as an MEP, and the intersection between race and sex shapes her politics. Soraya’s perspective is fully humanitarian, and this is in no way a cop out of claiming the label feminist: she fights for the humanity of Roma women and men, women around the world, to be recognised. The basic definition of human that shapes Soraya’s humanitarian politics does not stop at white and male – as is too often the case – and her passion for justice is wonderful to behold.

Soraya and Malin belong to different parties. They hold different perspectives, particularly with regard to the mainstreaming of gender. What strikes me is how their disagreements are in no way a barrier to them working together constructively, making the world a better place for women and girls. Many governments, especially the British Parliament, could stand to learn a great deal from their methods. Setting aside political point-scoring and one-upmanship not only brings integrity to politics, but brings about meaningful results.

I wasn’t prepared for how powerful an experience visiting the European Parliament would be. For the British women among the group, it is a poignant moment in the wake of Brexit. In the past, I have been ambivalent about the European Union – so concerned with reform that I didn’t necessarily appreciate the social good that it has brought about. It feels sad that I have only fully appreciated Britain’s membership of the European Union when we are on the cusp of losing it. The macho, isolationist politics of sovereignty have cost us a great deal.

That afternoon we begin learning about Appreciative Inquiry – far more exciting than it sounds. This session is, at heart, about stories and the role they play in providing us with self-definition. Storytelling is broken down into a process of three parts: storyteller, harvester, and listener. In groups of three, we take turns in each role and learn first-hand the ways in which narrative is shaped by those bearing witness in addition to the person telling the story. Sitting in the courtyard with Anna and Milena, the fountain splashing gently behind us, I am content. We share a great deal. It is good to listen. It is good to be heard.

Next, we meet local feminists involved in campaigns around Brussels, representing three organisations: Isala, the House of Women, and Garance. Isala is a team of volunteers working to prevent women in prostitution from becoming isolated, to stop society from turning a blind eye to their exploitation. Garance teaches self-defence in order to increase women’s agency against male violence, with the core aim of making women and girls feel safe, strong, and free as we occupy public space. The House of Women is, in some ways, reminiscent of Glasgow Women’s Library: it is motivated by empowering women in very practical terms. They seek to emancipate women through teaching new skills, encouraging independence, and advocate an openness that enables women to take up the public space to which we are entitled – as Adrienne Rich said, “When a woman tells the truth she is creating the possibility for more truth around her.” Hearing about their work helps us to break outside the Brussels bubble of political power and consider how the threads of feminist activism weave together to form what is a global movement.

As Soraya Post says, “you have to take your place in the room, set the agenda.” And the participants of AGORA ’16 are ready to do that. We prepare our own workshops and invite our fellow feminists to attend. The expanse of knowledge present and available in the room is extraordinary. From feminist podcasts to instructions on grassroots organising, a range of practical skills are covered. With discussions on the role choice plays in feminism and how to be a white ally to women of colour, the distance between feminist theory and practice is bridged with finesse.

The next morning I facilitate a workshop on intersectionality and co-existing identities in the feminist movement with Rosa, a Brazilian feminist with a flawless undercut and keen insight into geopolitics. The honesty women bring to the group is humbling, and I am profoundly touched that they are prepared to share so much of themselves in the discussion. The personal is political, a truth unavoidable when considering intersectional feminism. Running workshops is a very rewarding experience. I received facilitation training from Glasgow Women’s Library, who are always keen to upskill their volunteers, and have been putting on workshops since. It is a wonderful thing, to be able to do what you believe in. Afterwards, I go to a workshop facilitated by Hélène of Osez le Féminisme in which we share strategies for activism. My own plans for Sister Outrider slide into sharper focus.

We spend the afternoon at Amazone, where almost twenty women’s organisations hold office space. I decide to write, reflect, and take some time for myself in their sumptuous garden. Nearby, an impromptu workshop runs. It is a peaceful place. We return in the evening for our final party – bold lipstick and a black dress turns out to be a popular look. I am described as “witchy” – exactly the aesthetic I was striving for. Though we are openly critical of the beauty standards to which women are held, there is a lovely discussion about our lipstick choices, the ways in which our female friends have used it as a means of encouragement and support, a way to help us find little moments of joy. My own lipstick, Vintage Red, carries enough such history that every application brings me a measure of daring.

The wine flows, and so too does the conversation. It is lovely to be young, to be surrounded by other women as the night draws in, and to have the freedom of moving through Brussels as une femme seule. On such evenings, it feels as if anything is possible. And for the women of Young Feminist Summer School, it is.

After

My intention for Young Feminist Summer School had three parts: 1) Learn about effectively bridging the gap between theory and activism. 2) Support other women in their learning and be part of collective growth. 3) A bonus objective – have fun and meet new people. AGORA ’16 brought me all of these things and more.

In the space of five days, in the company of fifty women, my feminist politics have developed in ways that defied prediction. And I have grown a little more self-assured. After getting off the plane at Edinburgh Airport, returning home, I waited for the confidence AGORA brought out in me to fade – early on in the Summer School, I ceased questioning my right to speak as part of the group and the validity of my contributions – but it didn’t. The magic of Young Feminist Summer School lingers, continues to do its work. On the flipcharts papering the wall, a post-it note perfectly sums up why that is: “You will never walk alone! Because all AGORA will always support you.” That support has brought with it a degree of self-belief that continues to thrive.

Agora is a Greek word meaning marketplace – a public space in which not only goods but ideas were exchanged. And that sharing of ideas was exactly what we accomplished. That reciprocal learning was the highlight of Young Feminist Summer School, seeing the extraordinary depth and variety of knowledge other women brought and answering it with my own. And I became more aware of what it really is to be part of a collective unit, too – how powerful it is to be in a group of women, the way each and every one of us shapes the dynamic. This is something I have done in my home context, for a range of purposes, and found infinitely rewarding. That it is possible in an international setting too makes the world seem even more full of possibilities.

Young Feminist Summer School has also acted as an antidote to the Imposter Syndrome that shadows me through every achievement. In secondary school, I was certain that my university place would fall through. It didn’t. After completing my undergraduate degree, I was terrified I wouldn’t qualify to study for the Gender Studies MLitt. I did. This summer I was more than slightly concerned that the university would write to explain that offering me a place to undertake a research degree had actually been part of an elaborate practical joke. It wasn’t. Yet it never occurred to me to assume the inevitability of success. But, during AGORA, I found the courage to mention my PhD plans when people asked about my career and life. Nobody was surprised or disbelieving. They even thought my project – researching Black feminist activism in the UK – sounded exciting, worthwhile.

Something about the way these women responded to my ambitions, saw my hopes for the future as legitimate, enabled me to do the same. After Young Feminist Summer School, I didn’t let myself hesitate before talking about my PhD plans when asked – at a party filled with other feminists, at the Collect:If network for creative women of colour, with curious family friends, I mentioned my intention of undertaking further study. The more I spoke of those plans to other people, the more real they began to feel. The doubt was there every single time, but speaking about my studies made it a little more possible to see myself through the eyes of the women I was speaking to. Gradually, it got easier to ignore the voice of imposter syndrome and see success as the natural product of hard work and skill.

Looking back on Young Feminist Summer School, the thing that stands out most is how our politics shaped the way we treated each other, our dynamic as a group, and our relationship with public space. The compassion and trust within the group enabled real sisterhood. It also made being away from home, in another country previously unvisited, less intimidating than it otherwise could have been. Walking through the streets of Brussels as a group of fifty feminists was an adventure. Being together with other women, laughing and unafraid as we explored the city at night, was as much a novelty as a treat.

AGORA was a totally enriching experience: I am richer in travel, knowledge, experience, and – best of all – richer in friends. Since we left Brussels and returned to Britain, the UK AGORA group have stayed in regular and close contact. It’s a lovely support network, a group of understanding and encouraging feminist friends. We all have projects on the go – watch this space – and are planning to meet up again very soon, which is really exciting. I am grateful that Young Feminist Summer School brought us all together.

Daring to apply for AGORA ’16 is one of the best decisions I have ever made. It renewed my commitment to feminist politics at a time when I was growing weary. It reminded me of the joy found in working together with women to better the world around us. It gave me a positive vision for a feminist future. It let me be part of something so much bigger than myself. Watching my AGORA sisters grow and gain confidence over five days, consistently encouraging others to do the same, was a real honour. And being part of Young Feminist Summer School is an experience I will carry gladly for the rest of my life.

free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” There are times when the boldest and most radical thing you can do it stop talking and start listening. Really listening, with focus and curiosity. Learn about women whose lives are different to your own. Try to see the world through their eyes – let that empathy inform your own views, change your behaviour. Do not project yourself onto their stories, but rather treat the parallels between your struggles as a means of connection – a way to bridge difference.

free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” There are times when the boldest and most radical thing you can do it stop talking and start listening. Really listening, with focus and curiosity. Learn about women whose lives are different to your own. Try to see the world through their eyes – let that empathy inform your own views, change your behaviour. Do not project yourself onto their stories, but rather treat the parallels between your struggles as a means of connection – a way to bridge difference. Some have speculated that we are now living through the fourth wave of feminism, and they might be right. Technological advancements have propelled us into a digital era, making it possible to engage with and learn from women around the world. That information grows ever more accessible, that plural perspectives become all the more visible, brings a change for the better. New media has also shifted the pattern of who gets heard, whose voice is accepted as part of public discourse. Women of colour in particular benefit from the absence of traditional gatekeeping online, using social media and digital tools to build platforms for ourselves.

Some have speculated that we are now living through the fourth wave of feminism, and they might be right. Technological advancements have propelled us into a digital era, making it possible to engage with and learn from women around the world. That information grows ever more accessible, that plural perspectives become all the more visible, brings a change for the better. New media has also shifted the pattern of who gets heard, whose voice is accepted as part of public discourse. Women of colour in particular benefit from the absence of traditional gatekeeping online, using social media and digital tools to build platforms for ourselves. thing is that you look after yourself. Prioritise what you enjoy, activities that nourish you. The more involved with feminist politics you become, the more draining it has the potential to become – after all, you are living your politics and carrying that political struggle with you every day. Making space for yourself is not only valid, but good.

thing is that you look after yourself. Prioritise what you enjoy, activities that nourish you. The more involved with feminist politics you become, the more draining it has the potential to become – after all, you are living your politics and carrying that political struggle with you every day. Making space for yourself is not only valid, but good. Rebecca Bunce has a wonderful way of putting it: “As a feminist, look around the room and ask yourself ‘who isn’t here?’ Then ask what would it take to get that person here?” Never accept exclusion as the product of normality. Marginalisation is not a neutral act or process. By observing and challenging it, you have the power to prevent other people and their political struggles from being neglected.

Rebecca Bunce has a wonderful way of putting it: “As a feminist, look around the room and ask yourself ‘who isn’t here?’ Then ask what would it take to get that person here?” Never accept exclusion as the product of normality. Marginalisation is not a neutral act or process. By observing and challenging it, you have the power to prevent other people and their political struggles from being neglected.