Dear Shappi: An Open Letter on the Jhalak Prize

Dear Shappi,

I am looking forward to reading Nina is Not OK. I like your comedy very much, and am of the view that comedians have a gift for addressing the darker elements of life, so am keen to see how you highlight issues surrounding addiction and sexual assault through Nina’s story. Until the Jhalak Prize longlist was released, I hadn’t known about your novel but am very glad to have discovered it. Since last February – for almost an entire year – I have been anticipating that list and the selection books it would introduce me to. You see, I love nothing more than a good book. And the list has not disappointed!

Malorie Blackman is Children’s Laureate for very good reason – her books are impossible to put down and, for all the lessons they contain, never verge on moralising. After David Olusoga’s Black and British documentary series, which was rigorously researched and so full of heart, I can’t wait to read his book on the history of Black people living in Britain. Speak Gigantular had been on my wish list since friends raved about the beauty of Irenosen Okojie’s writing – I downloaded it as soon as the Jhalak Prize longlist was announced, and it is a delightful book. Then there is the treat of new books by unfamiliar authors: Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Kei Miller, you.

Malorie Blackman is Children’s Laureate for very good reason – her books are impossible to put down and, for all the lessons they contain, never verge on moralising. After David Olusoga’s Black and British documentary series, which was rigorously researched and so full of heart, I can’t wait to read his book on the history of Black people living in Britain. Speak Gigantular had been on my wish list since friends raved about the beauty of Irenosen Okojie’s writing – I downloaded it as soon as the Jhalak Prize longlist was announced, and it is a delightful book. Then there is the treat of new books by unfamiliar authors: Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Kei Miller, you.

The longlists of book prizes are like manna from heaven for bookworms. The quality of the books assured by the panel of judges, a great reading experience is pretty much guaranteed. For bookworms, prizes are like the literary equivalent of being gifted an all-inclusive holiday at a five star hotel. We know that these are books with the power to move, to provoke thought, to inspire feeling. These are books that will capture our hearts and quite possibly break them. These are books that will captivate our minds, stay in our heads long after the last page has been turned. The Man Booker, the Costa, the Bailey’s – each year, we bookworms look forward to those lists the same way we look forward to birthdays or bank holidays.

I was there at the Betsey Trotwood when the Jhalak Prize was announced. It was the launch party for Bare Lit Fest, Britain’s first literary festival centred entirely around the writing of Black and Asian authors. It was a weekend filled with brilliant books and the politics of liberation. Instead of the same old talk about change or resignation to the flaws of the publishing industry, this was action that promised results. Media Diversified and the founders of the Jhalak Prize had put their money where their mouth was. So had we, the people who bought tickets to attend and books once we were there. And that was really exciting to be part of.

I was there at the Betsey Trotwood when the Jhalak Prize was announced. It was the launch party for Bare Lit Fest, Britain’s first literary festival centred entirely around the writing of Black and Asian authors. It was a weekend filled with brilliant books and the politics of liberation. Instead of the same old talk about change or resignation to the flaws of the publishing industry, this was action that promised results. Media Diversified and the founders of the Jhalak Prize had put their money where their mouth was. So had we, the people who bought tickets to attend and books once we were there. And that was really exciting to be part of.

What stayed with me about Bare Lit was that not one single person of colour apologised for or questioned their seat on a panel, the legitimacy of their work being showcased. Along with new friendships and a suitcase full of books, I took a piece of that confidence back home to Glasgow. As people of colour we are forever expected to justify our successes, our voices, and even our very presence. We’re forever fighting this assumption (on the part of white people) that anything we achieve is down to the colour of our skin and not the merit of our work. The spectre of tokenism casts a shadow over the accomplishments we earn. And I’m really sad to hear that this concern over giving “ammunition” to racists caused you to withdraw from the Jhalak Prize. Being longlisted was a huge achievement and you deserved to own it. That Nina is Not OK is your first novel made it all the more impressive.

The tokenism/merit binary has a lot to answer for. It plays a key role in upholding racism in society. When people of colour don’t get ahead, it’s because we don’t work hard enough or just aren’t good enough. When people of colour do get ahead, it’s all down to positive discrimination. How hard we graft, the barriers we face with our work – these are never given the same scrutiny. Due to your stand-up I know you have come up against those barriers too, lost a role in a sitcom because the production team decided against casting an Iranian woman for the part of a nanny in a British series, and so I don’t blame you for how you handled being caught in a situation that has so many difficult layers.

The reason given for your withdrawal from the longlist was fear of alienating your audience. This is difficult to understand because surely, like all the other people who found your book through the Jhalak Prize, I am part of that audience. If anything, being shortlisted for a literary award broadens your audience by encouraging more people to read your books. Why reject the grounds for our interest in your novel? If the Jhalak Prize amounts to tokenism, our interest in the books listed is tokenistic too – a reductive view to take, given the superlatively high standard of the books on offer.

The reason given for your withdrawal from the longlist was fear of alienating your audience. This is difficult to understand because surely, like all the other people who found your book through the Jhalak Prize, I am part of that audience. If anything, being shortlisted for a literary award broadens your audience by encouraging more people to read your books. Why reject the grounds for our interest in your novel? If the Jhalak Prize amounts to tokenism, our interest in the books listed is tokenistic too – a reductive view to take, given the superlatively high standard of the books on offer.

Appreciation of good literature is what the Jhalak Prize is all about. And books by writers of colour – no matter how brilliant – are far less likely to get the appreciation they deserve. Men named Dave are statistically more likely to make it onto a best-seller list than any man or woman of colour. The publishing industry is overwhelmingly white, with under 1 in 10 of its employees identifying as people of colour – this impacts not only on whose stories are told, but the extent to which their promotion is prioritised and their authors supported.

The only audience likely to be alienated by Nina is Not OK being longlisted for the Jhalak Prize are white people who feel threatened by any direct celebration of the talents of people of colour – the sort of white people who reduce people of colour succeeding to tokenism rather than acknowledge the grounds on which that success is deserved. You worried that a white girl reading your book might think “oh right, so you’re not with me” because of your book being among nominations for the Jhalak Prize. But being with that white girl – having words with the potential to speak to her – is not and should not be at odds with any acknowledgement of your Iranian heritage. Good stories have universal value. “Should a reader be aware of someone’s ethnicity?” The alternative is that the reader assumes you are a white woman.

Obscuring your ethnicity might enable readers to pick up your book open to the idea that its content will be relatable, but it does nothing to unpick the perception that books written by white people speak universal truths and books written by people of colour are of limited relevance. If a reader picks up Nina is Not OK because they are intrigued by the premise, but puts it back down again because the author is Iranian, that amounts to racism.

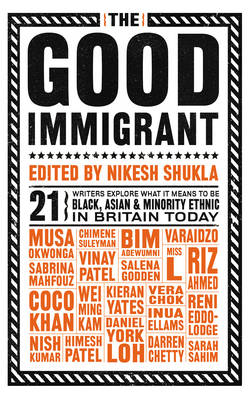

You spoke of the limitations imposed on immigrants in explaining your withdrawal, the hostility that immigrants face in Britain today. Nikesh Shukla, co-founder of the Jhalak Prize, edited an anthology on that very theme: The Good Immigrant. In that collection Darren Chetty’s essay draws from his experience as a primary school teacher, recalling a conversation in which two young pupils explain to one another that stories are only about white people. He analyses the prevalence of the idea that books are by and about white people, the implications of internalised racism in determining how Black and Asian children understand their position in the world. It is powerful stuff, and I highly recommend The Good Immigrant if you haven’t yet read it. By challenging the notion that a story must be by or about whiteness to be legitimate, we also challenge the underlying logic that dictates ownership of stories is white: the assumption that we are Other.

You spoke of the limitations imposed on immigrants in explaining your withdrawal, the hostility that immigrants face in Britain today. Nikesh Shukla, co-founder of the Jhalak Prize, edited an anthology on that very theme: The Good Immigrant. In that collection Darren Chetty’s essay draws from his experience as a primary school teacher, recalling a conversation in which two young pupils explain to one another that stories are only about white people. He analyses the prevalence of the idea that books are by and about white people, the implications of internalised racism in determining how Black and Asian children understand their position in the world. It is powerful stuff, and I highly recommend The Good Immigrant if you haven’t yet read it. By challenging the notion that a story must be by or about whiteness to be legitimate, we also challenge the underlying logic that dictates ownership of stories is white: the assumption that we are Other.

In spite of rather than because of your withdrawal from the Jhalak Prize longlist, I remain a part of your audience. However, as both a passionate bookworm and a Black woman, I now feel alienated because this decision makes it seem as though you value the comfort of your white audience above the engagement of Black and Asian readership. I do not feel as though you value me as a reader, or anybody else the Jhalak Prize has brought to your novel. Leaving the longlist was not a neutral act. It carried the potential to discourage just as surely as you imagined being present on the longlist might.

Your work is your property, under your control as creator. And that’s fine. I wish you every future success, Shappi, and hope that your writing continues to receive critical acclaim. And I leave you one final question about audience: is reaching white people who engage with your work in spite of their racism really more important than reaching people of colour who engage with your work from a place of solidarity?

Yours in sisterhood,

Claire