A brief foreword: a number of young women have contacted me in the last year, writing to ask about what it is like to be publicly radical in my feminism. That young women embrace radical feminism makes me optimistic for the future. That young women are too scared to be open about their radical feminism is utterly grim. And so this post is dedicated to every young woman bold enough to ask questions and challenge answers.

Update: this post has since been translated into French.

Why does radical feminism get so much bad press?

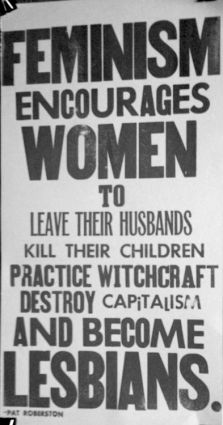

Radical feminism isn’t popular. That’s not exactly a secret – Pat Robertson’s infamous  claim that the feminist agenda “…encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism, and become lesbians” has set the tone for mainstream discussions of radical feminism. While Robertson’s perspective on radical feminism verges upon parody, his misogyny served with a side of blatant lesbophobia, it has also served to frame radical feminism as suspect.

claim that the feminist agenda “…encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism, and become lesbians” has set the tone for mainstream discussions of radical feminism. While Robertson’s perspective on radical feminism verges upon parody, his misogyny served with a side of blatant lesbophobia, it has also served to frame radical feminism as suspect.

If radical feminism can be written off as something sinister or dismissed as the butt of a joke, none of the difficult questions about the patriarchal structuring of society need to be answered – subsequently, power need not be redistributed, and members of the oppressor classes are saved from any challenging self-reflection. Rendering radical feminism monstrous is a highly effective way of shutting down meaningful political change, of maintaining the status quo. It is, therefore, predictable that the socially conservative right are opposed to radical feminism.

What’s often more difficult to anticipate is the venom directed towards radical feminism thought by the progressive left, which is assumed to support the politics of social justice. For women to achieve that justice, we must be liberated from patriarchy – including the constraints of gender, which is both a cause and consequence of male dominance. Yet, when one considers why that hostility emerged, it becomes sadly predictable.

Two factors enabled the left to legitimise its opposition to radical feminism. Firstly, the way in which liberation politics have been atomised by neoliberalism and replaced by the politics of choice (Walter). Personal choice, not political context, has become the preferred unit of feminist analysis. Therefore, critical analysis of personal choice – as advocated by radical feminism – has become a matter of contention despite its necessity in driving meaningful social change. The second factor is the gradual mainstreaming of a queer approach to gender. Instead of considering gender as a hierarchy to be opposed and abolished, queer politics position it as a form of identity, a part to be performed or subverted. This approach ultimately depoliticises gender, which is far from subversive, disregarding its role in maintaining women’s oppression by men. Feminists who are critical of gender are treated as the enemy, not gender in itself.

As a result, we find ourselves in a context where radical feminism is reviled across the political spectrum. On social media it feels as though radical feminists are just as likely to be abused by self-proclaimed queer feminists as we are men’s rights activists – the main difference between the two groups is that MRAs are honest about the fact they hate women.

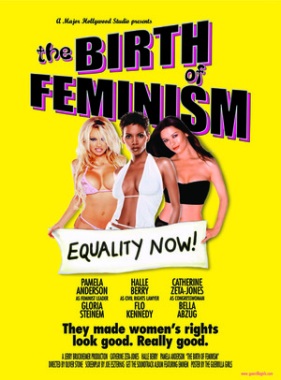

Young women in particular are discouraged from taking up the mantle of radical feminism. We have been raised on a diet of hollow buzzwords like ‘choice’ and ‘empowerment’, taught to pursue equality instead of liberation. From the ‘90s onwards, feminism has been presented as a brand accessed through commercialism and slogans instead of a social movement with the objective of dismantling white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks).

The third wave of feminism was marketed as a playful alternative to the seriousness of the second wave, which is routinely misrepresented as joyless and dour. Manifestations of women’s oppression, such as the sex industry, were repackaged as harmless choices with the potential to empower (Murphy). If young women are not prepared to accept pole dancing and prostitution as a harmless bit of fun, we risk being tarred by the same boring brush as the second wave; we are denied the label of “cool girl” and all the perks that come with remaining unchallenging to patriarchy. It is no coincidence that “pearl-clutching” and “prude”, accusations commonly directed towards radical feminists, are loaded with ageist misogyny – if radical feminists are presumed to be older women, the logic of patriarchy dictates that radical feminism must be boring and irrelevant. Both the desire for male approval that is drilled into girls from birth and the tacit threat of being associated with older women are used to keep young women from identifying with radical feminism.

The third wave of feminism was marketed as a playful alternative to the seriousness of the second wave, which is routinely misrepresented as joyless and dour. Manifestations of women’s oppression, such as the sex industry, were repackaged as harmless choices with the potential to empower (Murphy). If young women are not prepared to accept pole dancing and prostitution as a harmless bit of fun, we risk being tarred by the same boring brush as the second wave; we are denied the label of “cool girl” and all the perks that come with remaining unchallenging to patriarchy. It is no coincidence that “pearl-clutching” and “prude”, accusations commonly directed towards radical feminists, are loaded with ageist misogyny – if radical feminists are presumed to be older women, the logic of patriarchy dictates that radical feminism must be boring and irrelevant. Both the desire for male approval that is drilled into girls from birth and the tacit threat of being associated with older women are used to keep young women from identifying with radical feminism.

Liberal feminism has gained mainstream appeal precisely because it doesn’t threaten the status quo. If the powerful are comfortable with a particular form of feminism – liberal feminism, corporate “lean in” feminism, sex-positive feminism – it is because that feminism presents no challenge to the hierarchies from which their power stems. Such feminism can offer no meaningful social change and is therefore incapable of benefiting any oppressed class.

What are the negative consequences of being openly radical?

The backlash to being openly radical is the least fortunate element of it. I won’t lie: in the beginning, that can be intimidating. With time that fear will fade, if not dissipate. You will stop thinking “I couldn’t possibly say that” and start wondering “why didn’t I say that sooner?” The truth demands to be told, regardless of whether or not it happens to be convenient. Backlash and abuse directed towards radical feminists is a silencing tactic, plain and simple. Whether it comes from the conservative right or queer feminist left, that backlash (Faludi) is a means of silencing dissenting women’s voices. This realisation is freeing, both on a personal and political level. Personally, the good opinion of misogynists is of little value. Politically, it becomes clear that speaking out is an act of resistance. You will simply stop caring.

It takes energy, carrying the hatred people direct towards you – at some point you will realise that you’re not obliged to shoulder that burden and give yourself permission to set it down. Spend that energy on yourself instead. Read a book. Play an instrument. Talk with your mum. Do your nails. Binge-watch The Walking Dead. The time you spend worrying what people say about you, worrying if people like you, is a precious resource that cannot be recovered. Do not give them the gift of your worry – it is exactly what they want. Evict haters from your headspace.

You’re scared of being called a TERF. Let’s be real. That fear of being branded a TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) is why so many feminists are afraid to be openly radical, are increasingly unwilling to acknowledge gender as a hierarchy. And that’s alright to feel that fear – it’s meant to be scary. However, the fear needs to be put into perspective. The first time I was ever called “TERF” was for sharing a petition opposing female genital mutilation on Twitter. And when I pointed out that girls were at risk of FGM precisely because they were born female in patriarchy, that the girls who are cut are often of colour, often living within the global south (Spivak) – not exactly enjoying a wealth of cis privilege – the accusations only continued.

It spreads like wildfire. Because I did not repent for sharing that petition, because I did not condemn other women to save myself in the court of public opinion, it went on. That I am a lesbian (a woman who experiences same-sex attraction, i.e. disinterested in sex involving a penis) has only fanned the flames. My name can now be found on various shit lists and auto-block tools across the internet, which is pretty funny. Sometimes you do just have to laugh – it’s the only way to stay sane.

What’s less amusing is being told that I am dangerous. There is an insidious idea that any feminist who queries or critiques a queer perspective on gender is some sort of menace to society. Women who have devoted their adult lives to ending male violence against women are now described, without a trace of irony, as being violent. On a political level, it’s disturbing that disagreement over the nature of gender is positioned as violence within feminist discourse. There is an undeniably Orwellian quality to those opposing violence being described as violent, a double-speak perfected by queer politics. Framing gender-critical feminists as violent erases the reality that men perpetrate the overwhelming majority of violence against trans people and, in doing so, removes any possibility for men to be held accountable for that violence. Men are not blamed for their deeds, no matter how much harm they cause, whereas women are often brutally targeted for our ideas – in this respect, queer discourse mirrors the standards set by patriarchy.

Radical feminism is commonly treated as being synonymous with or indicative of transphobia, which is deeply misleading. The word transphobia implies a revulsion or disgust that simply is not there in radical feminism. I want all people identifying as trans to be safe from harm, persecution, and discrimination. I want all people identifying as trans to be treated with respect and dignity. And I do not know another radical feminist who would argue for anything less. Although radical and queer perspectives on gender are conflicting, this does not stem from bigotry on the part of the former. Abolishing the hierarchy of gender has always been a key aim of radical feminism, a necessary step in liberating women from our oppression by men.

As is often the case with structural analysis, it is necessary to think in terms of the oppressor class and the oppressed class. Under patriarchy, the male sex is the oppressor and the female sex the oppressed – that oppression is material in basis, reliant on the exploitation of female biology. It is impossible to articulate the means of women’s oppression without acknowledging the role played by biology and considering gender as a hierarchy – deprived of the language to articulate our oppression, language which queer politics deems violent or bigoted, it is impossible for women to resist our oppression. Therein sits the tension.

Ultimately, getting called names on the internet is a cost I am more than willing to pay if it is the price required to oppose violence against women and girls. Were it otherwise, I would be unable to call myself a feminist.

Ultimately, getting called names on the internet is a cost I am more than willing to pay if it is the price required to oppose violence against women and girls. Were it otherwise, I would be unable to call myself a feminist.

Did I choose to be ‘out’ as radical?

At no point did I make a decision to be publicly radical. Even in its most basic form, my feminism understood that ‘sex positivity’ and porn culture were repackaging women’s exploitation as ‘empowering’, that endless talk about choice only served to obscure the context in which those choices are made. I also recall being puzzled by the words sex and gender being used interchangeably in contemporary discourse – the former is a biological category, the latter is a social construction fabricated to enable the oppression of women by men. Seeing gender treated as an amusing provocation or, worse, something innate in our minds, was deeply disconcerting – after all, if gender is natural or inherent, so too is patriarchy. I was conscious that my views were considered old-fashioned but, although it was slightly isolating, not troubled by the tension between me and what I now know to be liberal feminism.

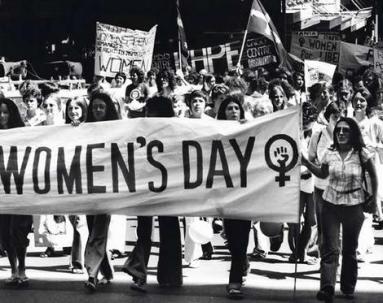

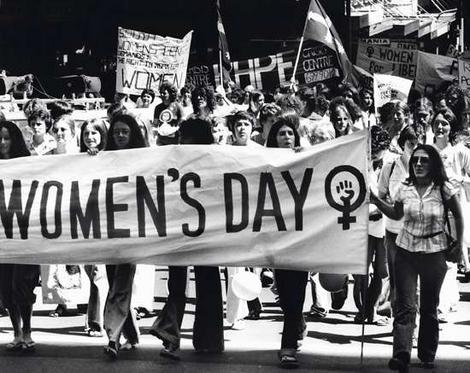

It was only through finding radical feminist Twitter that I realised plenty of  contemporary feminists thought with the same framework, that these ideas did not exist solely in books that had been written some twenty years before I was born. I do not say this to disparage the feminism of the 1970s, but rather to point out that there was an almost wishful nostalgia to my conceptualisation of that era and the politics it embodied. The second wave felt impossibly far away – thinking about it was like thinking of a party for which you are already decades too late. It felt like that feminism, of radical ideas and action, was gone. Now I realise that is exactly what young women are conditioned to think in the hope that we will grow complacent and accept our oppression instead of challenging it at the root.

contemporary feminists thought with the same framework, that these ideas did not exist solely in books that had been written some twenty years before I was born. I do not say this to disparage the feminism of the 1970s, but rather to point out that there was an almost wishful nostalgia to my conceptualisation of that era and the politics it embodied. The second wave felt impossibly far away – thinking about it was like thinking of a party for which you are already decades too late. It felt like that feminism, of radical ideas and action, was gone. Now I realise that is exactly what young women are conditioned to think in the hope that we will grow complacent and accept our oppression instead of challenging it at the root.

Having grown up and developed my ideas, it now seems unlikely I would have found a place had I been of that context – as lesbian feminists go, I am fairly apolitical with regard to sexuality: I’m still not convinced it is possible to choose to be a lesbian, do not know that I would choose to be a lesbian even if the option had been there (there is an undeniable appeal to being slightly more ‘of’ than Other), and oppose the notion that bisexual women are being half-hearted in their feminist praxis because they will not ‘become’ lesbians. Yet, I would not have found my way into those conversations without radical feminist Twitter.

As my political consciousness was catalysed by radical feminist Twitter, a community that continues to challenge and delight me, it seemed natural to participate in that discourse publicly. I was more concerned about developing my ideas – learning from and, later on, teaching other women – than any potential reaction. Perhaps naïvely, I had not fully considered the convenience of closeting my politics. Being connected to radical feminist discourse, engaging with its ideas and the women behind them, was always the priority. I did not initially consider the possibility of acquiring public profile, and now consider it as a largely unfortunate by-product of my participation in feminist discourse as opposed to something worth maintaining in its own right – perhaps why I do not self-censor for the sake of popularity.

Are there professional consequences for being a radical feminist?

It depends on what you do. Countless radical feminists have been reported to their employers for differentiating between sex and gender. Being openly radical when you work in the women’s sector carries a particular risk. Similarly, women who are academics or hold some form of institutional power are in a delicate position, faced with the dilemma of jeopardising a career or speaking out. I know dozens of radical feminists who achieve more social good for other women by saying nothing explicitly radical whilst doing the most extraordinary, necessary work. None of that work would be possible if those women chose to die on the hill of gender politics. A direct result of that would be other women losing out – from literacy classes to policy on male violence, there would be very real consequences if covertly radical women lost their positions. There are times when staying quiet is the smarter option, particularly in conversations about gender politics, and I will not condemn women who make that tactical decision.

My career is freelance – in this respect, being directly accountable only to myself is useful. That being said, a freelance career is dependent on organisations being willing to commission my writing or workshops. Becoming a pariah is fairly counterproductive in that respect. At points people have contacted (or at least threatened to contact) places where I study, volunteer, and write. Nothing has ever come of it. Why? Their accusations are false. I have nothing to hide about feminism – there is no shameful secret at the heart of my sexual politics. I will only ever say what I believe in, what I can back up with evidence, what a substantial body of feminist theory supports.

Being able to speak with conviction and follow through when questioned is crucial. Those qualities are also what appeal to the people and organisations who hire me. A recurring theme with commissions: at least one person within the organisation has covertly voiced support for my radical feminism. Radical feminism is less of an anathema than we are made to believe.

I am commissioned to produce work that I believe in. Nothing my detractors have said or done changes that fact. To quote Beyoncé, the best revenge is your paper.

How do non-radical feminists react?

Badly. Not always, but often. Some of the most rewarding and thought-provoking engagements are with women who are not radical feminists yet engage in good faith. Unfortunately, those interactions are in the minority.

Abuse from strangers, while it can be frightening, is something to which I have grown habituated. I report it to the relevant authorities and move on. Following the most concentrated period of abuse I have endured, it was not the threats that weighed on my mind, but the responses of queer and liberal feminists. A number openly celebrated my abuse and its consequences. Theirs is the type of feminism that is opposed to racism, misogyny, homophobia, etc. up until the point those prejudices damage someone whose politics do not align with their own. That was disconcerting. Be prepared for those moments. Be prepared to lose false friends, too.

It’s a strange position to be in. If the label TERF has ever been applied to you, it strips away something of your humanity in the eyes of the wider public. You are no longer viewed as a worthy recipient of empathy or even basic human decency. This isn’t surprising, because TERF is often used in conjunction with violent threats and graphic descriptions of abuse. It legitimises violence against women.

TERF functions something like “witch” in The Crucible. Only by condemning other women can you avoid that condemnation yourself. There is a frantic edge behind the panic it spreads. There are plenty of feminists who will be prepared to monster you to save their own reputations. They are not worth your respect, let alone the time it would take to puzzle out their motives.

It is also worth considering the responses of feminists who are not publicly radical. Women routinely tell me that I am saying what they believe, express gratitude that I speak out, tell me that my words resonate. And this is gratifying, yes, but it is also isolating. An almost supernatural courage is projected onto openly radical women, an exceptionalism that is often used by other women to justify their silence. Glosswitch often speaks about this phenomenon, and she is right – it would be far more rewarding if the women who offer private support would publicly claim their own radical politics instead, provided they are in a position to do so.

Bibliography

bell hooks. (2004). The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

Susan Faludi. (1991). Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women

Miranda Kiraly & Meagan Tyler (eds.). (2015). Freedom Fallacy: The Limits of Liberal Feminism

Gayatri Spivak. (1987). In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics

Natasha Walter. (2010). Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism

Hibo Wardere. (2016). Cut: One Woman’s Fight Against FGM in Britain Today

THANK YOU SO MUCH

The more I read about radical feminism, the more informed, articulate and therefore confident I feel.

It is great to see that many of the problematics around sex/ gender/ patriarchy/ all those things I did not know how to formulate are in fact theorized by radical feminism.

I feel bolder in my radical feminism every day and optimistic about the future when I read articles like yours. When I know there are others thinking like me out there, and I feel readier to confront this ridicule trend of playboy/lipstick/pseudo-multicultural feminism, however one wants to call it.

I am sorry what I write does not make much sense but I am so excited hehehe.

Thanks again,

All the best!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I cannot believe I am not fighting against sexist pigs anymore because neoliberal feminists are doing the job for them!

LikeLike

You have emboldened me. I will share this article on social media. You are the best and I am a hypocrite for not speaking out. Thank you for the kick in the a**.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My goal wasn’t to kick anybody’s ass, but I am delighted you feel bolder now. Good luck!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Brilliant article 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is great! It’s a really good summary of radical feminism that I can pass on to people who want to know more. Thanks for writing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am heartened reading this article. I am an old radical feminist and lesbian feminist. I am sorry so many young women will miss out on the wonderful culture we had built with bookstores, restaurants and bars. Hopefully new ways and spaces will open and there will be more women of color than ever in this movement. It is so important that we keep spreading the knowledge and ideas of radical feminism and stay with the material reality that there are two sexes and the gender roles assigned to them constitute a hierarchy with men on top. Only an active women’s movement focused on our issues has ever made the gains we need. The pop neo-lib feminism that has taken over has not taken us further but decimated our solidarity and left the gains we made in jeopardy. Despite the lack of coverage in our mainstream media there is growing movement of young radical feminists.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Very informative and helpful. You write and think with great lucidity. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed the article-very clear, on point.

I have a question; how to find radical feminists near you? I feel like meeting likeminded people but no matter what I type in google nothing comes. It makes me feel very isolated as you wrote.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am stuggling with the same problem. I’m American and live in Tennessee, soon to move to Indiana. Every blog I find is based in another country and/or hasn’t been active for years. All I can think of us to start my own group. I have one friend who I can rely on and I’m going to build on that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great article! I appreciated your reflection that we are constantly being told to think of radical feminism as ancient and extinct – I remember being told the very same thing back in the 90s! It’s a way of willing ideas out of existence.

The question of professional consequences is also a worrying one and of course the ultimate irony is that it mostly only affects women in “progressive” workplaces! In my own job, I have to be careful how I approach this stuff, but I’m sneaking real feminism in where I can, and your writings inspire me to do better.

LikeLiked by 1 person