Dispatches from the Margins: Lesbian Connection & the Lavender Menace

A brief foreword: Every so often, a lesbian will write a message that deeply moves me. They usually start out by thanking me for defending lesbian sexuality in a time when it is contested and then move on to express something deeper – a feeling of loneliness and despair brought about by the way lesbians are treated in progressive spaces, be they feminist or queer. Women around the world carry this feeling, and have reached out to me to express this sense of isolation it creates. I’m also carrying that sadness and, while I can’t alleviate it in myself or others, am capable of unpacking some of the factors that cause it.

Dedicated to Anne. You’re not alone.

I’m losing friendships with straight Black women. And that loss is painful. But it’s not hard to grasp the reason for it. The feminist connections between me & hetero women have never been entirely easy: there’s a kind of distance that comes into being, and obscures shared points of understanding, through their responses to my sexuality. Yet still it is difficult, because there is place and kinship in those friendships along with a lot of joy. For the benefit of those who have never been forced to weigh up the risk of racism before building a relationship, I will also point out that there is a great spiritual ease in knowing that you will not experience anti-Blackness from a friend, because she too is Black. The friendship becomes a place of safety. So much is possible when that soft, vital part of you is open instead of pre-emptively guarding against the likelihood of racism.

Quite a few of my friendships with white lesbians, some fledgling and others fully formed, have disintegrated too – over those women’s approach, or lack of, to race. Although experiencing racism is never a picnic, I am used to receiving it from white women and have adjusted my expectations accordingly. It’s less of a pressing concern because I am not particularly invested in whiteness. I learned from a very early age that when you are surrounded by a group of white people, it’s a question of when rather than if the racism is going to manifest. There is no reason to imagine that white lesbians are the exception to whiteness by virtue of their sexuality. However, I think the reason deep friendship with white lesbians remains an ongoing possibility for me is that their radical feminist politics can enable the critical, reflective work required to unlearn racism.

For the last year I have felt pulled between the expectations that straight Black women and white lesbian women have put upon my feminism. At multiple points, it seems as  though what one group values about my feminism is a point of contention for the other. In the eyes of a number of straight Black women in my life, I am too radical – my unwillingness to divorce gendered aspects of the personal from the political creates a rift. With some of the white lesbians in my life, I am insufficiently radical – too invested in exploring grey areas and the pesky politics of race to fit with their understanding of lesbian feminism.

though what one group values about my feminism is a point of contention for the other. In the eyes of a number of straight Black women in my life, I am too radical – my unwillingness to divorce gendered aspects of the personal from the political creates a rift. With some of the white lesbians in my life, I am insufficiently radical – too invested in exploring grey areas and the pesky politics of race to fit with their understanding of lesbian feminism.

You can’t please everybody, and I haven’t the slightest desire to try. No person who lives authentically can be universally liked. Yet this split does not feel like a mere matter of liking, and neither does it feel coincidental. In fact, it can usually be traced back to the positionality of everyone involved.

At one of the conferences for women of colour I attended last year, I had the pleasure of eating lunch around a table with two other Black women, fellow speakers. Their company was at once thrilling and reassuring: because they saw my perspective as being relevant to the event and were interested in my ideas, it was possible to untie the knots in my stomach for long enough to avail myself of some delicious stew and give a talk unimpeded by nerves. There’s magic in how being seen by other Black women enables one to shake off the imposter syndrome that develops through being made continuously Other. I hope my belief in those women, my excitement in their ideas, provided a similar kind of affirmation. It was uplifting. We talked between sessions, as is the way of things. As we started to feel familiar, one asked whether I had a man and children.

It was a weird moment. I had imagined the only way I could look more obviously lesbian was by wearing a Who Killed Jenny Schecter? t-shirt. But not everyone reads lesbian presentation, least of all heterosexuals. For a second I hesitated, conscious that my honesty would remove some of the assumptions of similarity that had enabled our tentative bond. I didn’t know how to explain, and didn’t want to expose the part of myself that dreams of one day having and being a wife – less still the fledgling hope that one day I’ll have sufficiently stable mental health for us to raise a daughter together. It was painful to think the women with whom I’d shared understanding might find these aspirations alien or repellent.

Audre taught me the power in a name, in claiming the word lesbian. She never let that part of herself be erased or dismissed, even when it would have been convenient for her as a woman and as a feminist. I wouldn’t – couldn’t – deny it either, but at the same time I never relish spending the mental energy required to come out to a relatively unknown person. The risk and reward don’t necessarily balance out in within those transient connections, or any other for that matter, but within those fleeting friendships it can seem like a lot to give. Coming out isn’t just a one-time thing, as Mary Buckheit once wrote. It’s the work of a lifetime, repeated over and over again – assuming it is safe enough to do so in the first place.

I’ve been out for a few years now. In that time, I’ve become a bit too familiar with that little fission – the peculiar sensation when someone’s perception of me changes in the moment they learn that I’m a lesbian. And I felt it in that moment. There was a before, and there was an after. While I do generally share an affinity with my fellow Black women, more than any other demographic, issues of gender and sexuality do bring some tensions to the surface. The obvious solution would be to invest more time & energy in Black lesbians. Unfortunately, Scotland’s Black population density is pretty low – which makes finding other Black lesbians even harder. There are a lot of white lesbians, a few lesbians of colour, and a tiny number of Black lesbians in my life. For now, at least, I must play the hand geography has dealt me. This involves following a lot of Audre Lorde’s advice and using difference creatively – as something to be explored and learned from.

Broadly speaking, the feminism of straight women and lesbian women tends to be different. Straight and lesbian are not the only two categories into which a woman’s sexuality may fall, and certainly not the only feminist standpoints worth considering, but this particular difference requires some exploration. I’m not inclined to go down the purist path of a certain political lesbianism and claim that one is stronger or worthier somehow than the other – feminism isn’t a competition, and the variety in women’s perspectives only ever enriches the movement. All the same, there are differences in those feminisms brought about by a difference between how heterosexual and lesbian women experience the world.

Straight women are sheltered by the social support system that accompanies heterosexuality (Frye, 1983), not exposed to the precariousness of a lesbian life. Every significant relationship developed during my adult life falls into the category of “fictive” kinship, nameless ties not recognised as real by a heteronormative society. Lesbian connections are positioned as lesser, unreal, unnatural. Conversely, straight women are rewarded for forging ties of “true” kinship through marriage and blood, ties which society deems legitimate because they exist in relation to men. Building a life in which men are central – prioritised, desired, and considered essential companions – is fundamentally different to building a life that is woman-centric. Each path holds contrasting limitations and possibilities for how a woman lives her feminism, which is not necessarily a bad thing for the movement. It is the approach to difference, as opposed to the difference in itself, which determines the depth of what is possible between women.

…we sometimes find it difficult to deal constructively with the genuine differences between us and to recognize that unity does not require that we be identical to each other. Black women are not one great vat of homogenized chocolate milk. We have many different faces, and we do not have to become each other in order to work together. – Audre Lorde, I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities

I think that as mainstream feminism’s scope has narrowed from a collective to an individual scale, becoming more about choice than structural analysis, space for women to explore the political significance of their lived realities has dwindled. There is a lack in contemporary feminism, a lack which has led us to stop pushing for liberation and instead settle for tepid notions of equality. As a result, feminism has an ever-shrinking scope and we are encouraged to abandon feminist practice that goes beyond what is comfortable or easily explained. Those complex avenues of thought, which lead us to ask immensely complicated questions about the relationship between the personal and the political, are not places women receive great encouragement to explore. And in a way it’s convenient, because we are spared the uncertainty held within radical possibilities – but we also lose out on the freedom those possibilities offer. If we pick comfort over challenge, the safety of the familiar over the potential of the unknown, the power of the feminist movement dissipates: a radical restructuring of society remains beyond our reach.

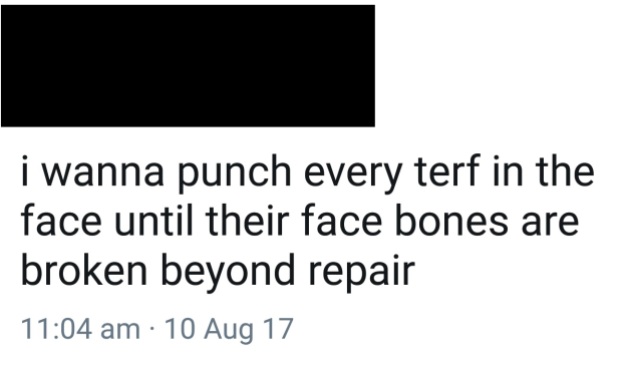

The area where feminists have become most restricted, hemmed in by fear and inhibition, is gender. Nothing will change to the benefit of women or trans/non-binary identifying people until an armistice is reached on the so-called TERF wars. Just as the sex wars blighted feminism of the 1980s, the TERF wars undermine the modern day movement. I believe that a willingness to ask difficult questions, of ourselves and each other, is the only way feminists holding any belief about gender will be able move past this stalemate. Naturally, this involves thinking challenging and uncomfortable thoughts. To practice radical honesty, instead of thinking only what falls within the walls of convenience and straightforwardness, will at least allow feminists of differing perspectives the space to connect and understand one another better.

In calling for greater honesty around the subject of gender, in advocating a deeper radicalism, I do not mean cruelty. Scrutinising gender does not and should not require cruelty towards anyone trapped by that hierarchy. If anything, radical practice demands compassion in every direction. And there is a definite shortfall of compassion within conversations about gender and sexual politics.

There are a great many things to find upsetting about how gender discourse now happens. What I find hardest to bear is watching friendships with straight Black women unravel, fray, and snap, pulled apart by gender politics. It hurts. It’s weighing on my mind. And I don’t have the energy to resist anymore. There is a particular malice that is projected onto the motives of lesbian women critiquing gender. Responses to lesbian feminist perspectives on gender often fail to recognise that it is a system oppressing us twice over, on account of both our sex and sexuality. By some twist of logic, the harm gender does to lesbians is erased – though marginal on multiple axes, we are assumed to be the oppressive force within an LGBT context.

The way straight feminists approach queer politics suggests that a significant number do not have a solid understanding of what LGBT+ organising is actually like for the women who do fit under the rainbow umbrella. In collective organising of the 1970s and ‘80s, lesbians were marginalised by the unchecked misogyny of gay men (ed. Harne & Miller, 1996). A lot of LGB spaces were male-centric, treating masculinity as the default way to be gay or bisexual. Women’s lived realities and political interests were not a priority unless actively centred by lesbian feminists (Jeffreys, 2003). While it’s easy to get caught up in the narrative of lesbians being deliberately difficult, it’s important to remember that cooperation meant being complicit in your own oppression instead of resisting it. When the T was added onto LGB, concerns of sexuality and identity were rather clumsily amalgamated – which means there are even more competing interests under the rainbow umbrella. Somewhat predictably, women’s concerns – especially the concerns of lesbian women – have become ever more peripheral. In today’s queer context, we’re more likely to be told the term lesbian is outdated or invited to re-examine the parameters of our sexuality than receive a modicum of solidarity. Straight feminists, who don’t live or organise under the rainbow umbrella, are perhaps not best placed to pass judgement on the lesbian women who do.

Life under the rainbow isn’t all fun and games. These conflicts directly affect our lives in ways that can be hard to carry, and we’re yet to reach consensus on any possible solution. Lesbian women and gay men were recently lambasted for suggesting that we return to organising around issues of sexuality – an unfortunate backlash, in my opinion. Collective organising around sexuality and collective organising around identity would enable each respective group to pursue their political needs more effectively. Without the in-fighting, there would be potential for a new and true mode of solidarity  unhindered by the tensions of today. Where there’s common ground, there would be room for coalition. Where there’s none, there would at least be an absence of competition. I’ve seen more than one queer activist make the case that “it should be just the TQ+” as “the LGB part has already been normalized into heteronormativity.” Although this perspective doesn’t account for radical lesbian and gay organising, there is a case to be made for untangling the alphabet soup.

unhindered by the tensions of today. Where there’s common ground, there would be room for coalition. Where there’s none, there would at least be an absence of competition. I’ve seen more than one queer activist make the case that “it should be just the TQ+” as “the LGB part has already been normalized into heteronormativity.” Although this perspective doesn’t account for radical lesbian and gay organising, there is a case to be made for untangling the alphabet soup.

Queer politics have brought about this myth that gays and lesbians have achieved liberation. It goes the same way as rhetoric used (often by men) to explain why feminism is now redundant: women are basically equal now. Women are not equal to men, much less liberated from them – don’t bother trying to convince me otherwise until the pandemic of men’s violence against women and girls comes to an end. Patriarchy remains part of society’s foundation. Gender, which exists as a cause and consequence of patriarchy, gives rise to heterosexism and homophobia. It’s all connected.

In a recent conversation with my mother, she spoke about why she has remained at the same place of work for nearly two decades. The company has excellent policies safeguarding the rights of gay and lesbian employees – she told me that, even if people didn’t like her sexuality, she felt confident they couldn’t express anti-lesbian sentiment towards her because of strictly enforced consequences for discrimination. I know that’s hardly the ultimate struggle, and there is a certain privilege in having been able to build a lengthy career with one organisation, but it broke my heart a bit that whether or not she would be supported against lesbophobia factored into my mum’s decision making process in choosing her job. (Yes, she is a lesbian, which makes me lucky enough to be a second generation gay.) To be a lesbian does not bring a woman any great power or socioeconomic privileges – in fact, it does the opposite. Which is why it’s disheartening that mainstream feminism has ceased to treat us as worthy recipients of compassion.

Lesbian women are not viewed as “natural” subjects of empathy, despite being marginalised, because we do not live “natural” lives. Our way of living – which involves loving, desiring, and prioritising women – is not simply outside of heterosexist values, but a direct challenge to those values (Rich, 1980). The lack of empathy we receive from straight women is influenced and enabled by lesbophobia. I invite straight feminists to consider why their go-to assumption is that a lesbian feminist perspective on gender is motivated by malice, and to ask themselves why it is easy to imagine an innate cruelty in lesbian women.

Increasingly, I see straight feminists treating their lesbian sisters in a way that they could never condone behaving towards their trans siblings. Perhaps this disparity in compassion is because trans-identifying people do not overtly challenge the foundations of a heterosexual feminist life, whereas sharing spaces with lesbian feminists invariably brings the institution of heterosexuality into sharper focus – and in so doing raises uncomfortable questions. At times straight feminists speak about certain lesbian feminist theorists in such a way that you would be forgiven for thinking they described repeat violent offenders, not women in their sixties and seventies. Linda Bellos, a committed Black lesbian feminist, was vilified for speaking about the conflict between lesbian and queer politics. If we do not speak about it openly and honestly, that horrible tension is only going to grow – but I fear that scapegoating lesbian feminists is easier than engaging with what lesbian women have to say.

Lesbians are more likely to be described as unfeeling or – more ridiculous still – dangerous than straight feminists who analyse gender as a social harm. We are pathologised even within the feminist movement, lavender menaces once more. Radical feminists – many of whom are lesbian – consider gender as a vehicle for violence against women and girls. Therefore, we aim to eliminate gender in order to liberate women and girls from violence. Being a gender abolitionist has nothing to do with cruelty or prejudice, and everything to do with wanting to make this world a better, fairer place – somewhere all women and girls can thrive. I wish that more straight women could find ways to critique the gender politics of any lesbian feminism without resorting to Othering. There is scope for disagreement without subtly pathologising lesbian desires or perspectives.

An ever-growing number of Tweets muse about the correlation between lesbian  sexuality and “TERF” politics, including such dubious pearls of wisdom such as this: “repeated use of the word ‘lesbian’ is also a dog whistle for TERFs.” If even saying lesbian can be taken as proof of transphobia, something has clearly gone wrong in this conversation. As Black feminist theory has long held (Hill Collins, 1990), self-definition is an essential step in the liberation of any oppressed group – including lesbians. And yet straight feminists are often willing to be complicit in lesbian erasure or, worse still, deny that erasure is happening even as lesbians challenge it.

sexuality and “TERF” politics, including such dubious pearls of wisdom such as this: “repeated use of the word ‘lesbian’ is also a dog whistle for TERFs.” If even saying lesbian can be taken as proof of transphobia, something has clearly gone wrong in this conversation. As Black feminist theory has long held (Hill Collins, 1990), self-definition is an essential step in the liberation of any oppressed group – including lesbians. And yet straight feminists are often willing to be complicit in lesbian erasure or, worse still, deny that erasure is happening even as lesbians challenge it.

For the most part I try not to write in anger, but there is something uniquely galling about being asked to consider how lesbian sexuality upholds oppressive practices by women who are married to and raising children with men. Lesbians experiencing same-sex attraction is casually problematised in conversations about gender – often by women who are exclusively attracted to the opposite sex and consider partnership with men to be the “natural” trajectory of their lives. And because relations between men and women are positioned as “natural” in heteropatriarchy, they are not subject to a fraction of the scrutiny that lesbian (and, increasingly, gay) sexuality faces. It’s sad but predictable that heterosexuality is rarely critiqued as part of gender discourse, even as expression of lesbian sexuality is treated as evidence of transphobia.

As the tension between gender and sexual politics grows, the mainstream feminist movement tends to forget that lesbians are women doing our best to survive life under patriarchy – perhaps even to break free from it if we’re lucky. Lesbians are not and never have been the women mainstream feminism is concerned with protecting: our vulnerability, unlike that of heterosexual women, evokes no great sympathy. Straight women treat lesbians as expendable to the feminist movement, although we have always been at the heart of feminism, in order to create enough distance to safely avoid being branded lesbian themselves.

The terror of Black Lesbians is buried in that deep inner place where we have been taught to fear all difference – to kill it or ignore it. Be assured: loving women is not a communicable disease. You don’t catch it like the common cold. Yet the one accusation that seems to render even the most vocal straight Black woman totally silent and ineffective is the suggestion that she might be a Black Lesbian. – Audre Lorde, I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities

There is irony in straight women condemning lesbian feminists for our gender politics: it is, of course, our very refusal to live within the confines of gender that makes us the legitimate targets of their Othering. The distance between straight and lesbian feminists stems from het women’s failure to use that difference as a mine of creative energy. Difference can function as a source of solutions, not problems, if we are bold enough to seize upon it.

Ultimately, it’s not difficult to see why so many straight Black feminists are receptive to the notion of gender as identity. White lesbians ask me about this routinely – why so many heterosexual Black feminists have embraced queer gender politics – and my answer revolves around the following points. White women’s gender politics have historically been antagonistic towards Black women, compounding the racist oppressions we experience. Black women know what it is to be positioned outside of the acceptable, recognised standard of womanhood. Therefore, some sense parallels between the struggles of being born into Black womanhood and finding transwomanhood. The shared pains and challenges that come with being an outsider act as a bridge. What’s more, single-issue, gender-only feminism was only ever a viable option for the most privileged white women. Gender might not even be the most keenly felt form of oppression that manifests in a Black woman’s life, and so accepting its continuation may seem like a viable political compromise when it brings about fresh potential for solidarity.

The part I do not understand – or rather, do not want to understand – is the reluctance of some straight Black women to extend the same empathy or willingness to understand towards their lesbian sisters. Shared similarities between straight and lesbian Black women do not mean that I will hesitate to challenge an Othering approach to our differences. But it is not a criticism that I relish having to make. With certain women, there is a choice to be made: I can have my principles, or I can have those friendships. Principle wins every time. It’s simple, but also excruciatingly complicated.

Bibliography

Marilyn Frye. (1983). The Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory

Lynne Harne & Elaine Miller, eds.. (1996). All the Rage: Reasserting Radical Lesbian Feminism

Patricia Hill Collins. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment

Sheila Jeffreys. (2003). Unpacking Queer Politics

Audre Lorde. (1988). A Burst of Light: And Other Essays

Audre Lorde. (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches

Adrienne Rich. (1980). Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence

Gender is a hierarchy that enables men to be dominant and conditions women into subservience. As gender is a fundamental element of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks, 1984) it is particularly disconcerting to see elements of queer discourse argue that gender is not only innately held but sacrosanct. Far from being a radical alternative to the status quo, the project of “queering” gender only serves to replicate the standards set by patriarchy through its essentialism. A queer understanding of gender does not challenge patriarchy in any meaningful way – rather than encouraging people to resist the standards set by patriarchy, it offers them a way to embrace it. Queer politics have not challenged traditional gender roles so much as breathed fresh life into them – therein lies the danger.

Gender is a hierarchy that enables men to be dominant and conditions women into subservience. As gender is a fundamental element of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks, 1984) it is particularly disconcerting to see elements of queer discourse argue that gender is not only innately held but sacrosanct. Far from being a radical alternative to the status quo, the project of “queering” gender only serves to replicate the standards set by patriarchy through its essentialism. A queer understanding of gender does not challenge patriarchy in any meaningful way – rather than encouraging people to resist the standards set by patriarchy, it offers them a way to embrace it. Queer politics have not challenged traditional gender roles so much as breathed fresh life into them – therein lies the danger. gendered even before birth, serves to divide the sexes into a dominant and subservient class. Feminism recognises that biological sex exists while opposing essentialism, opposing the idea that sex dictate who or what we are capable of being as humans. Feminism asserts that our character, qualities, and personality are not defined by whether we are male or female. Conversely, queer theory argues that one set of traits is inherently masculine and another set of traits is inherently feminine, and our

gendered even before birth, serves to divide the sexes into a dominant and subservient class. Feminism recognises that biological sex exists while opposing essentialism, opposing the idea that sex dictate who or what we are capable of being as humans. Feminism asserts that our character, qualities, and personality are not defined by whether we are male or female. Conversely, queer theory argues that one set of traits is inherently masculine and another set of traits is inherently feminine, and our

Despite talk of queer community, an alliance between members of the LGBT+ alphabet soup, homophobia has always been at the root of queer politics. Queer ideology emerged as backlash to lesbian feminist principles, which advocated radical social change through the transformation of personal lives (Jeffreys, 2003). The political interests of lesbian women and marginalised gay men – primarily the abolition of gender roles – were dismissed within queer spheres. Individualism precluding any concentrated focus on feminist and gay liberation politics, which queer discourse began to describe as old-fashioned, dull, or anti-sex.

Despite talk of queer community, an alliance between members of the LGBT+ alphabet soup, homophobia has always been at the root of queer politics. Queer ideology emerged as backlash to lesbian feminist principles, which advocated radical social change through the transformation of personal lives (Jeffreys, 2003). The political interests of lesbian women and marginalised gay men – primarily the abolition of gender roles – were dismissed within queer spheres. Individualism precluding any concentrated focus on feminist and gay liberation politics, which queer discourse began to describe as old-fashioned, dull, or anti-sex.

When I pointed out that your words were lesbophobic, you claimed this could not be because you are “queer as the day is long.” Since you are queer as opposed to lesbian, it is not for you to decide what is lesbophobic or not. Being queer does not inoculate you against homophobia or, indeed, lesbophobia. Queer is an umbrella term, a catch-all which may encompass all but the most rigid practice of heterosexuality. It is not a stable category or coherent political ideology, as anything considered even slightly transgressive may be labelled queer. Queer is a deliberately amorphous expression, avoiding specific definitions and fixed meanings. It need not relate to the politics of resistance, and indeed cannot relate to the politics of resistance because queer lacks the vocabulary to positively identify oppressed and oppressor classes. Queer seeks to subvert the dominant values of society through performativity and playfulness as opposed to deconstructing those values by presenting a radical alternative to white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy. Queer is

When I pointed out that your words were lesbophobic, you claimed this could not be because you are “queer as the day is long.” Since you are queer as opposed to lesbian, it is not for you to decide what is lesbophobic or not. Being queer does not inoculate you against homophobia or, indeed, lesbophobia. Queer is an umbrella term, a catch-all which may encompass all but the most rigid practice of heterosexuality. It is not a stable category or coherent political ideology, as anything considered even slightly transgressive may be labelled queer. Queer is a deliberately amorphous expression, avoiding specific definitions and fixed meanings. It need not relate to the politics of resistance, and indeed cannot relate to the politics of resistance because queer lacks the vocabulary to positively identify oppressed and oppressor classes. Queer seeks to subvert the dominant values of society through performativity and playfulness as opposed to deconstructing those values by presenting a radical alternative to white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy. Queer is